What Really Happened To The Apostles?

Share

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED TO THE APOSTLES?

Sean McDowell

“Even though they were crucified, stoned, beheaded, dragged, and skinned alive, eleven of the twelve apostles of Jesus proclaimed his resurrection until their dying breaths, refusing to recant under pressure from the authorities. Since they would not have died for a lie, the resurrection must be true.”

If you have preached a sermon on the apostles or followed popular-level apologetics over the past few decades, you have probably encountered some version of this claim. Growing up I heard it regularly and found it quite convincing. After all, why would the apostles of Jesus have died for their faith if it weren’t true?

Yet the question was always in the back of my mind, What is the evidence the apostles actually died as martyrs for their belief in the risen Jesus? A few years ago I began researching this question as part of my doctoral studies. And what I have found is both surprising and insightful.

My goal in this article is to offer a succinct summary of what we can know about the missionary journeys and fates of the apostles, and then consider what evidence this provides for the truth of the resurrection. But first we begin with the question: Is there evidence the apostles even existed?

DID THE APOSTLES EXIST?

Three main arguments have been made for the historicity of the Twelve as a group Jesus personally formed. First, references to the Twelve appear in various sources and forms (e.g., Mk 3:14-19; Jn 6:67-71; 1Co 15:5). The different lists of names for the Twelve indicate they may represent independent tradition.

Second, by the criterion of embarrassment, the early church very unlikely would have invented a story of Jesus personally choosing Judas to be a member of the Twelve. This is one reason historical Jesus scholar E.P. Sanders considers the existence of the Twelve among the “(almost) indisputable facts about Jesus.”1

Third, if the tradition of the Twelve were invented, one would expect early church records to be filled with examples of the Twelve’s powerful influence and leadership in the church. Yet the opposite is the case. Neither Luke nor Paul has much to say of the Twelve. While the lack of early information on the Twelve makes it difficult to determine the historicity of their martyrdom accounts, this same absence is an indication that the group was not a mere invention of the early church.

Richard Bauckham recently completed an onomastic study of Jewish names of this time that lends additional support to the authenticity of the Twelve.2 Among Jews in first-century Palestine there were a small number of very popular names and a large number of rare ones. As would be expected, if the tradition of the Twelve were reliable, a combination of common and rare names would be on the lists. This is exactly what we find. Taken together, these facts make it highly likely the Twelve existed as a special group of disciples who formed an inner circle around Jesus.

Pentecost by Juan Bautista Maino (1581-1649). Fifty days after Passover AD 33, the apostles and other believers were baptized with the Holy Spirit. Three thousand were added to their number. The result was that “everyone was filled with awe, and many wonders and signs were being performed through the apostles” (Ac 2:43).

There is good reason to believe the apostles existed, but what evidence is there that they actually engaged in missionary endeavors? We turn to that question next.

DID THE APOSTLES ENGAGE IN MISSIONARY WORK?

There is little doubt the apostles first witnessed their faith to Israel (e.g., see Mk 6:7-13; Mt 10:5-25; Lk 9:1-6). But what evidence is there that they engaged in missionary work beyond Israel? There is both internal and external evidence the apostles engaged in missionary work after their departure from Jerusalem.

Internal Evidence

Jesus makes it clear that his apostles are to go beyond Israel: “Beware of them, because they will hand you over to courts and flog you in their synagogues. You will even be brought before governors and kings because of me, to bear witness to them and to the Gentiles” (Mt 10:17-18; Mk 13:9; Lk 21:12-13). Jesus warns his followers that their preaching will be deeply opposed and they will be brought before the highest authorities in the land. The emphasis on “governors and kings” indicates that Jesus is no longer speaking of their present mission in Judea, but the future mission to the Gentiles outside Palestine.

The book of Acts shows the beginnings of the Christian mission. One of Luke’s primary purposes is to show the development of Christian evangelism among the people of Israel to a larger secular sphere that will entail witness to governors and kings. A number of passages in Acts demonstrate that the followers of Jesus are to take the message of Jesus throughout the world (e.g., Acts 1:8; 8:4-40; 9:23-35; 10:34-43; 11:19-22; 13:1-2).

External Evidence

There is also external evidence that the apostles left Jerusalem to engage in missionary work. The earliest extra-biblical testimony can be found in 1 Clement 42:3-4b (ca AD 95-96):

“Having therefore received their orders, and being fully assured by the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, and established in the word of God, with full assurance of the Holy Ghost, they went forth proclaiming that the kingdom of God was at hand. And thus preaching through countries and cities.”

The Preaching of Peter, an early second century text, reports a similar journey for the apostles:

“Jesus says to the disciples after the resurrection, ‘I have chosen you twelve disciples, judging you worthy of me,’ whom the Lord wished to be apostles, having judged them faithful, sending them into the world to the men on the earth, that they may know that there is one God.”

From the end of the first century onward, the consistent testimony from church fathers is that the apostles engaged in missionary work. There is no good reason to doubt these accounts. Thus, there is good reason to believe the apostles engaged in missionary work beyond Israel, but what do we know about the individual apostles?

INDIVIDUAL APOSTLES

Peter. The book of Acts portrays Peter preaching and teaching in Jerusalem (2:14-41), Judea, Galilee, Samaria (9:31-32), and Caesarea (10:34-43). First Peter was written to exiles of the dispersion in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia (1:1). In his book The Life and Witness of Peter, Larry Helyer concludes, “In short, it is likely that Peter evangelized among Jews and Greeks in the western Diaspora, including Rome, over a period of at least sixteen or seventeen years and possibly more.”

St. Peter in Tears by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-1682)

The traditional view is that Peter was crucified in Rome during the reign of Nero in AD 64 to 67. The earliest evidence for the martyrdom of Peter comes from John 21:18-19, which was written no later than thirty years after Peter’s death, and possibly before AD 70. Commentators unanimously agree that this passage predicts the martyrdom of Peter. Bart Ehrman concludes, “It is clear that Peter is being told that he will be executed (he won’t die of natural causes) and that this will be the death of a martyr.”3 Other early evidence for Peter’s martyrdom can be found in writings such as Clement of Rome (1 Clement 5:1-4), Ignatius (Letter to the Smyrneans 3:1-2), The Apocalypse of Peter, The Ascension of Isaiah, The Acts of Peter, The Apocryphon of James, Dionysius of Corinth (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.25.4), and Tertullian (Scorpiace 15, The Prescription Against Heresies 36). The early, consistent, and unanimous testimony is that Peter died as a martyr.

The claim that Peter was crucified upside-down is historically possible, but it first appears in the legend-filled text The Acts of Peter (ca AD 180-190), and so is difficult to trust with any degree of confidence.

Paul. Beginning in Arabia, Paul took at least three missionary journeys throughout his life (2Co 11:32-33; cp. Ac 9:19-25). His trips included Cyprus and southern Asia Minor (Ac 13-14); Macedonia, Philippi, Thessalonica, Athens, and Corinth (Php 4:15-16; 1Th 2:2; Ac 16-18); Antioch, Greece, and Ephesus (Gl 2:11; Ac 18:18-20:38); and Rome via Jerusalem (Ac 21-28:31). Paul certainly intended to visit Spain (Rm 15:24,28) and some interpret Clement of Rome (ca AD 96) as indicating Paul traveled to Spain: “After preaching both in the east and west, he gained the illustrious reputation due to his faith, having taught righteousness to the whole world, and come to the extreme limit of the west, and suffered martyrdom under the prefects” (1 Clement 5:5). Some believe Paul evangelized Britain.

Saint Paul by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660)

The traditional view is that Paul was beheaded in Rome during the reign of Nero in AD 64 to 67. Scripture does not directly state his martyrdom, but there are hints in both Acts and 2 Timothy 4:6-8 that Paul knew his death was pending. The first extrabiblical evidence is found in 1 Clement 5:5-7 (ca AD 95-96) in which Paul is described as suffering greatly for his faith and then being “set free from this world and transported up to the holy place, having become the greatest example of endurance.” While details regarding the manner of his death are lacking, the immediate context strongly implies that Clement was referring to the martyrdom of Paul. Other early evidences for the martyrdom of Paul can be found in Ignatius (Letter to the Ephesians 12:2), Polycarp (Letter to the Philippians 9:1-2), Dionysius of Corinth (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.25.4), Irenaeus (Against Heresies 3.1.1), The Acts of Paul, and Tertullian (Scorpiace 15:5-6). The early, consistent, and unanimous testimony is that Paul died as a martyr.

James, the brother of Jesus. Although not one of the Twelve, James was an apostle who had seen the risen Jesus (Gl 1:19; 1Co. 15:7). He is consistently painted in church tradition as being extraordinarily righteous (e.g., Eusebius, Church History 2.23). James was one of the first leaders of the Jerusalem church (Acts 15:14-21). Unlike the members of the Twelve, there are no early accounts of his missionary journeys beyond Jerusalem.

The first evidence for the death of James comes from Josephus in his Antiquities 20.197-203 (ca AD 93/94). Unlike the Testimonium Flavianum,4 this passage is largely undisputed by scholars. It allows the dating of James’s execution to AD 62, since Josephus places his death between two Roman procurators, Festus and Albinus. According to this account, the high priest Ananus had James stoned to death. The death of James is also reported by Hegesippus (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.23.8-18), Clement of Alexandria (Hypotyposes Book 7), The First Apocalypse of James (Gnostic text), and the Pseudo-Clementines (Recognitions 1:66-1.71). The case for the martyrdom of James is strengthened by the fact that there are Christian (Hegesippus, Clement of Alexandria), Jewish (Josephus), and Gnostic (First Apocalypse of James) sources that affirm it within a century and a half from the event. This suggests an early, widespread, and consistent tradition regarding the fate of James.

But why was James killed? If he were killed for political reasons unrelated to his faith, he would hardly qualify under the traditional definition of a martyr.

James was most likely viewed as enticing people to follow other gods (see Dt 13:9-10). Darrell Bock explains:

What Law was it James broke, given his reputation within Christian circles as a Jewish Christian leader who was careful about keeping the Law? It would seem likely that the Law had to relate to Christological allegiances and a charge of blasphemy. This would fit the fact that he was stoned, which was the penalty for such a crime, and parallels how Stephen was handled as well.5

Sculpture of James the Brother of Jesus

Thomas. The traditional story is that Thomas travelled to India where he was speared to death. Although some Western scholars are skeptical, the Eastern Church has consistently held that Thomas ministered in India and died there as a martyr. There are records of travel from the Middle East into India during the first century, so there is no reason to doubt Thomas could have made it there. Positive evidence comes from the Acts of Thomas (ca AD 200-220), which records the traditional story of his fate. Many write it off as entirely fictional, but the mere fact that it contains historical figures, such as Thomas, Gondophares, Gad, and possibly even Habban and Xanthippe, Mazdai, and the city of Andrapolis, indicates that it is not entirely divorced from a historical memory. While there is not any written history in India prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, there certainly was a sense of history passed down orally through poems, songs, customs, and celebrations of the people. The St. Thomas Christians, for instance, are utterly convinced that their heritage traces back to the apostle Thomas himself, including introduction of the Syriac or Chaldaic (East Syriac) language which is used for liturgical purposes. The community has preserved many antiquities that testify to their traditions.

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Titian (1490-1576)

Andrew. Andrew is perhaps best known as the brother of Peter. Every time he appears in the Gospel of John, he is bringing someone to Jesus. Andrew brings three people to Jesus, including Peter (1:41-42), a small boy who has fish and loaves (6:8), and some Greeks who want to worship Jesus (12:20-22). He unmistakably has a missionary mindset from the moment he meets Jesus, which the historical record seems to bear out. There are a wide variety of traditions regarding his missionary endeavors including Judea, Africa, central Asia, Scythia (southern Russia), and Europe. Given the commission of Jesus (Mt 28:19-20; Ac 1:8), Andrew’s missionary mindset, and the existence of such an array of traditions, there is good reason to believe Andrew was a missionary who advanced the gospel of Christ.

The earliest written record of the martyrdom of Andrew comes from the Acts of Andrew (ca AD 150-210). This text concludes with Andrew speaking to the cross and then demanding the executioners kill him. Many later written accounts exist of the death of Andrew, but they all trace back through The Acts of Andrew. Hippolytus on the Twelve (ca third century) may possibly preserve an independent tradition of his death when it describes Andrew as “crucified, suspended on an olive tree, at Patrae.” But we cannot be sure. The Acts of Andrew clearly contains legendary embellishment, but it is plausible that it was connected to a reliable tradition about Andrew’s death.

Saint Andrew by José de Ribera (1591-1652)

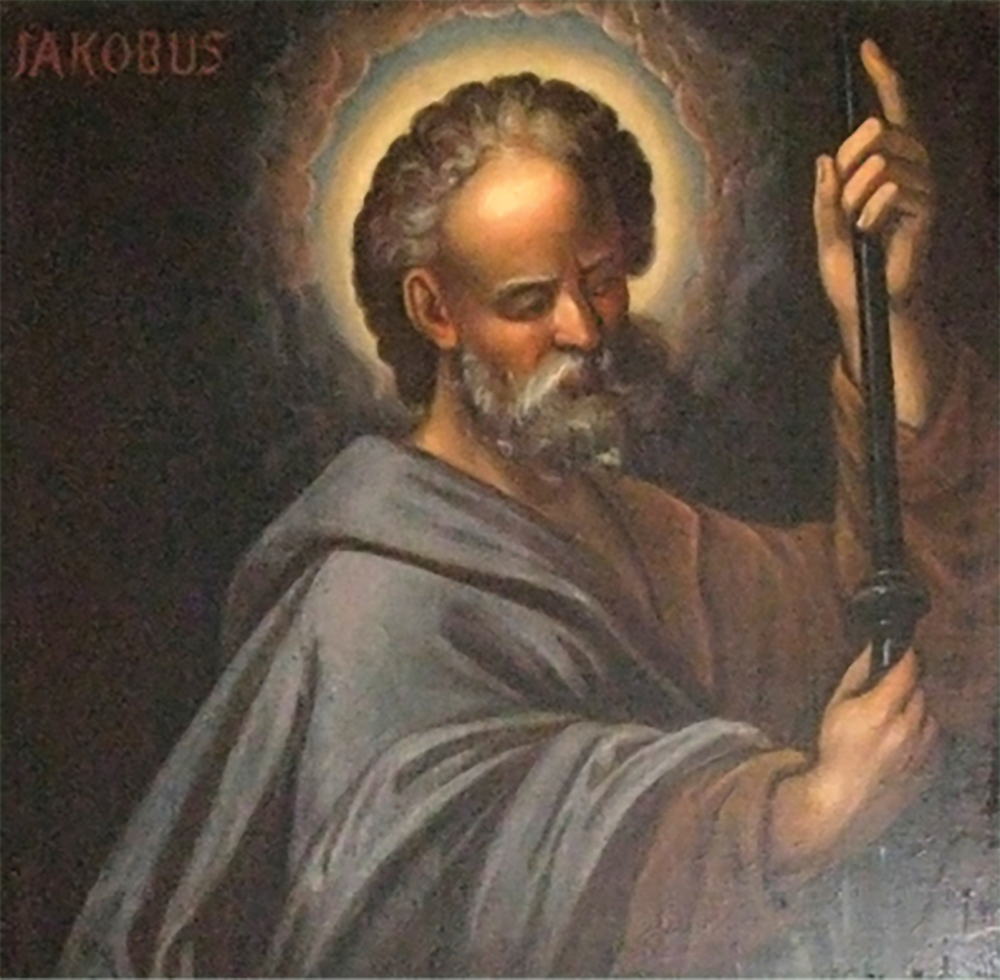

The Rest of the Apostles. Except for James the son of Zebedee (whose fate is described in Ac 12:2), and his brother John, it is difficult to know with certainty what happened to the remaining apostles. The evidence is late, filled with legendary accretion, and traditions were often confused between some of the apostles (such as Matthew with Matthias, Philip the apostle with Philip the evangelist, and the various Jameses).

James, son of Zebedee by Johann Friedrich Glocker (1718-1780)

St. Bartholomew by Rembrandt (1606-1669)

The claim that Bartholomew was skinned, for instance, doesn’t show up until about AD 500. Does that make it false? Not necessarily. But it diminishes the claim’s plausibility. As for Thaddeus, the western tradition (ca AD sixth/seventh century) claims that he was martyred, whereas the eastern tradition (ca AD fifth century) describes him dying peacefully. It is difficult—if not impossible—to know which of these accounts, if any, is true. And this is the case for the rest of the apostles.

While there are no early accounts that any of the apostles recanted, we simply don’t know how many of them were killed for their testimony about Christ. But here is what we do know about the apostles:

1. Their beliefs were based on personally seeing the risen Jesus (1Co 15:3-7; Ac 1:22). The apostles had a resurrection faith.

2. They were willing to suffer and die for their beliefs. Jesus not only taught them to expect persecution (e.g., Mt 10:16-23; Mk 13:9; Lk 6:22-23; Jn 15:18-27), but they were personally threatened, beaten, and thrown into prison for their public proclamation of the risen Jesus. And yet they refused to back down (Ac 4:1-20; 5:27-32).

3. There is good reason to believe the apostles engaged in missionary work in Jerusalem, Judea, and in various places around the world with full knowledge of what their proclamation could cost them.

4. There is evidence that at least some of the apostles died as martyrs, including Peter, Paul, James the son of Zebedee, and James the brother of Jesus.

In conclusion, the early and consistent testimony of the New Testament and early sources is that the apostles were witnesses of the risen Jesus and willingly suffered for the proclamation of the gospel. While alone it does not prove the resurrection is true, it does show the apostles sincerely believed it. They were not liars.

1 E.P. Sanders, Jesus and Judaism (London: SCM, 1985), 101.

2 Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 67-88.

3 Bart Ehrman, Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene: The Followers of Jesus in History and Legend (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 84.

4 Antiquities 18.3.3.

5 Darrell Bock, Blasphemy and Exaltation in Judaism: The Charge against Jesus in Mark 14:53-65 (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2000), 196 n. 30.