The Theology of the New Testament

Share

The Theology of the New Testament

New Testament theology as a discipline is a branch of what scholars call “biblical theology.” Systematic theology and biblical theology overlap considerably, since both explore the theology found in the Bible. Biblical theology, however, concentrates on the historical story line of the Bible and explains the various steps in the progressive outworking of God’s plan in redemptive history. In this article some of the main themes of NT theology are presented.

Already but Not Yet

The message of the NT cannot be separated from that of the OT. The OT promised that God would save his people, beginning with the promise that the seed of the woman would triumph over the seed of the Serpent (Gen. 3:15). God’s saving promises were developed especially in the covenants he made with his people: (1) the covenant with Abraham promised God’s people land, seed, and universal blessing (Gen. 12:1–3); (2) the Mosaic covenant pledged blessing if Israel obeyed the Lord (Exodus 19–24); (3) the Davidic covenant promised a king in the Davidic line forever, and that through this king the promises originally made to Abraham would become a reality (2 Samuel 7; Psalm 89; 132); and (4) the new covenant promised that God would give his Spirit to his people and write his law on their hearts, so that they would obey his will (Jer. 31:31–34; Ezek. 36:26–27).

As John the Baptist and Jesus arrived on the scene, it was obvious that God’s saving promises had not yet been realized. The Romans ruled over Israel, and a Davidic king did not reign in the land. The universal blessing promised to Abraham was scarcely a reality, for even in Israel it was sin, not righteousness, that reigned. John the Baptist therefore summoned the people of Israel to repent and to receive baptism for the forgiveness of their sins, so that they would be prepared for a coming One who would pour out the Spirit and judge the wicked.

Jesus of Nazareth represents the fulfillment of what John the Baptist prophesied. Jesus, like John, announced the imminent arrival of the kingdom of God (Mark 1:15), which is another way of saying that the saving promises found in the OT were about to be realized. The kingdom of God, however, came in a most unexpected way. The Jews had anticipated that when the kingdom arrived, the enemies of God would be immediately wiped out and a new creation would dawn (Isa. 65:17). Jesus taught, however, that the kingdom was present in his person and ministry (Luke 17:20–21)—and yet the foes of the kingdom were not instantly annihilated. The kingdom did not come with apocalyptic power but in a small and almost imperceptible form. It was as small as a mustard seed, and yet it would grow into a great tree that would tower over the entire earth. It was as undetectable as leaven mixed into flour, but the leaven would eventually transform the entire batch of dough (Matt. 13:31–33). In other words, the kingdom was already present in Jesus and his ministry, but it was not yet present in its entirety. It was “already—but not yet.” It was inaugurated but not consummated. Jesus fulfilled the role of the servant of the Lord in Isaiah 53, taking upon himself the sins of his people and suffering death for the forgiveness of their sins. The day of judgment was still to come in the future, even though there would be an interval between God’s beginning to fulfill his promises in Jesus (the kingdom inaugurated) and the final realization of his promises (the kingdom consummated). Jesus, who has been reigning since he rose from the dead, will return and sit on his glorious throne and judge between the sheep and the goats (Matt. 25:31–46). Hence, believers pray both for the progressive growth and for the final consummation of the kingdom in the words “your kingdom come” (Matt. 6:10).

The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) focus on the promise of the kingdom, and John expresses a similar truth with the phrase “eternal life.” Eternal life is the life of the age to come, which will be realized when the new creation dawns. Remarkable in John’s Gospel is the claim that those who believe in the Son enjoy the life of the coming age now. Those who have put their faith in Jesus have already passed from death to life (John 5:24–25), for he is the resurrection and the life (John 11:25). Still, John also looks ahead to the day of the final resurrection, when every person will be judged for what he or she has done (John 5:28–29). While the focus in John is on the initial fulfillment of God’s saving promises now, the future and final fulfillment is in view as well.

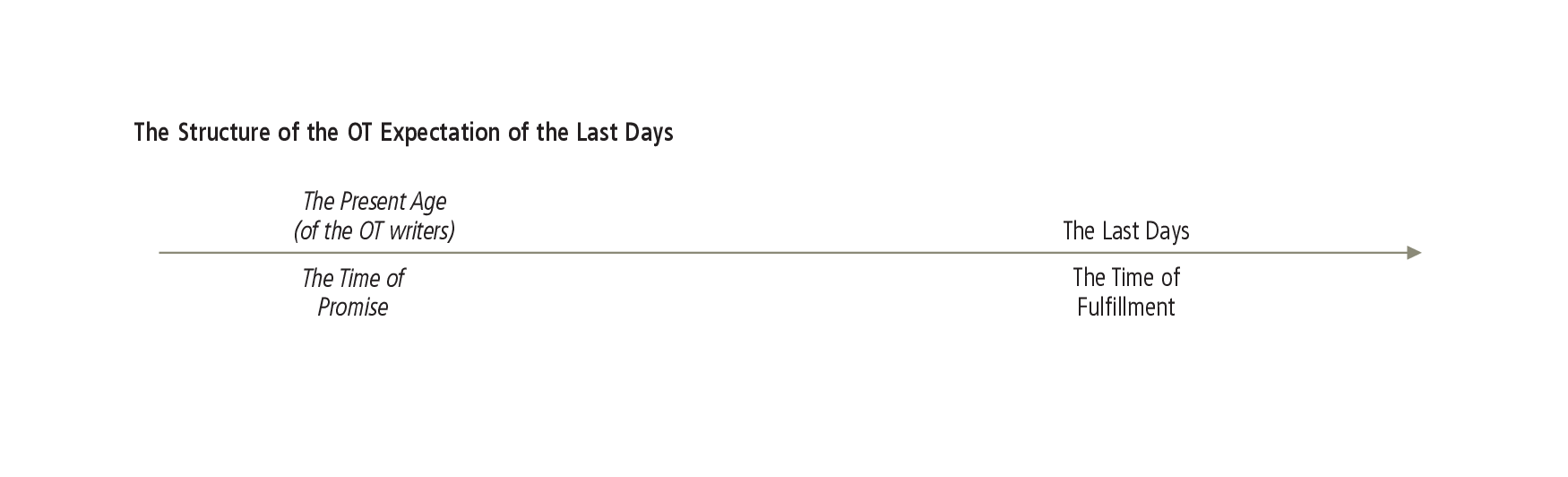

The already-not-yet theme dominates the entire NT and functions as a key to grasping the whole story (see chart). The resurrection of Jesus indicates that the age to come has arrived, that now is the day of salvation. In the same way the gift of the Holy Spirit represents one of God’s end-time promises. NT writers joyously proclaim that the promise of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit has been fulfilled (e.g., Acts 2:16–21; Rom. 8:9–16; Eph. 1:13–14). The last days have come through Jesus Christ (Heb. 1:1–2), through whom we have received God’s final and definitive word. Since the resurrection has penetrated history and the Spirit has been given, we might think that salvation history has been completed—but there is still the “not yet.” Jesus has been raised from the dead, but believers await the resurrection of their bodies and must battle against sin until the day of redemption (Rom. 8:10–13, 23; 1 Cor. 15:12–28; 1 Pet. 2:11). Jesus reigns on high at the right hand of God, but all things have not yet been subjected to him (Heb. 2:5–9).

Fulfillment through Jesus Christ, the Son of God

The NT highlights the fulfillment of God’s saving promises, but it particularly stresses that those promises and covenants are realized through his Son, Jesus the Christ.

Who is Jesus? According to the NT, he is the new and better Moses, declaring God’s word as the sovereign interpreter of the Mosaic law (Matt. 5:17–48; Heb. 3:1–6). Indeed, the Law and the Prophets point to him and find their fulfillment in him. Jesus is the new Joshua who gives final rest to his people (Heb. 3:7–4:13). He is the true wisdom of God, fulfilling and transcending wisdom themes from the OT (Col. 2:1–3). In the Gospels, Jesus is often recognized as a prophet. Indeed, Jesus is the final prophet predicted by Moses (Deut. 18:15; Acts 3:22–23; 7:37). Jesus’ miracles, healings, and authority over demons indicate that the promises of the kingdom are fulfilled in him (Matt. 12:28), but his miracles also indicate that he shares God’s authority and is himself divine, for only the Creator-Lord can walk on water and calm the sea (Matt. 8:23–27; cf. Ps. 107:29). Jesus is the Messiah, who brings to realization the promise that One would sit on David’s throne forever. Recognizing Jesus as the Messiah is fundamental to all the Gospels and the missionary preaching of Acts, and is an accepted truth in the Epistles and Revelation.

The stature of Jesus shines out in the NT narrative, for he authoritatively calls on others to be his disciples, summoning them to follow him (Matt. 4:18–22; Luke 9:57–62). Indeed, a person’s response to Jesus determines his or her final destiny (Matt. 10:32–33; cf. 1 Cor. 16:22). Jesus is the Son of Man who will receive the kingdom from the Ancient of Days (Dan. 7:13–14) and will reign forever. The Gospels emphasize, however, that his reign has been realized through suffering, for he is also the servant of the Lord who has atoned for the sins of his people (Isa. 52:13–53:12; Mark 14:24; Rom. 4:25; 1 Pet. 2:21–25).

This One who atones for sin is fully God and divine. (See The Person of Christ.) He has the authority to forgive sins (Mark 2:7). Various NT occurrences of the word “name” indicate Jesus’ divine status: people prophesy in his name (Matt. 7:22) and are to hope in his name (Matt. 12:21), and salvation comes in his name alone (Acts 4:12). But the OT establishes that human beings are to prophesy only in God’s name, hope only in the Lord, and find salvation only in him; thus, such use of Jesus’ name indicates his divinity.

The Greek translation of the OT (the Septuagint) identifies Yahweh as “the Lord.” In quoting or alluding to OT texts that refer to Yahweh, the NT authors often apply the title “Lord” to Jesus and evidently use it in that strong OT sense (e.g., Acts 2:21; Phil. 2:10–11; Heb. 1:10–12). The title is therefore another clear piece of evidence supporting Christ’s divinity. Jesus is the image of God (Col. 1:15; cf. Heb. 1:3), is in the very form of God, and is equal to God, though he temporarily surrendered some of the privileges of deity by being clothed with humanity so that human beings could be saved (Phil. 2:6–8). Jesus as the Son of God enjoys a unique and eternal relationship with God (cf. Matt. 28:18; John 20:31; Rom. 8:32), and he is worshiped just as the Father is (cf. Revelation 4–5). His majestic stature is memorialized by a meal celebrated in his memory (Mark 14:22–25) and by people being baptized in his name (Acts 2:38; 10:48). The Son of God is the eternal divine Word (Gk. Logos) who has become flesh and has been identified as the man who is God’s Son (John 1:1, 14). Finally, in a number of texts Jesus is specifically called “God” (e.g., John 1:1, 18; 20:28; Rom. 9:5; Titus 2:13; Heb. 1:8; 2 Pet. 1:1). Such texts involve no trace of the heresy of either modalism or tritheism. Rather, such statements contain the raw materials from which the doctrine of the Trinity was rightly formulated. (See The Trinity.)

New Testament theology, then, is Christ-centered and God-focused, for what Christ does on earth brings glory to God (John 17:1; Phil. 2:11). The NT particularly focuses on Jesus’ work on the cross, by which he redeemed and saved his people. The story line in each of the Gospels culminates in and focuses on Jesus’ death and resurrection. Indeed, the narrative of Jesus’ suffering and death consumes a significant amount of space in the Gospels, indicating that the cross and resurrection are the point of the story. In Acts we see the growth of the church and the expansion of the mission, as the apostles and others proclaim the crucified and resurrected Lord. The Epistles explain the significance of Jesus’ work on the cross and his resurrection, so that believers are enabled to grasp the height, depth, breadth, and width of the love of God (Rom. 8:39). The significance of the cross is explained in relation to themes such as new creation, adoption, forgiveness of sins, justification, reconciliation, redemption, sanctification, and propitiation. Woven together, these themes teach that salvation comes from the Lord, and that Jesus as the Christ has redeemed his people from the guilt and bondage of sin.

The Promise of the Holy Spirit

Bound up with the work of Christ is the work of the Holy Spirit. Jesus promised to send the Spirit to those who are truly his disciples (John 14:16–17, 26; 15:26), and he poured out the Spirit on his people at Pentecost (Acts 2:1–4, 33) after he had been exalted to the right hand of the Father. The Spirit was given to bring glory to Jesus Christ (John 16:14), so that Christ would be magnified as the great Savior and Redeemer. Luke and Acts in particular emphasize that the Spirit is given for ministry, so that the church is empowered to bear witness to Jesus Christ. At the same time, having the Spirit within is the mark of a person belonging to the people of God (Acts 10:44–48; 15:7–9; Rom. 8:9; Gal. 3:1–5). The Spirit also strengthens believers, so that they are enabled to live in a way that is pleasing to God. Transformation into Christlikeness is the Spirit’s work (Rom. 8:2, 4, 13–14; 2 Cor. 3:18; Gal. 5:16, 18).

The Human Response

Because of sin, all humanity stands in need of the salvation that Christ brings. The power of sin is reflected in the biblical story line, for even Israel as the chosen people of the Lord lived under the dominion of sin, showing that the written law of God by its own power cannot deliver human beings from bondage to sin. Paul emphasizes that sin and death are twin powers that rule over all people, so that they stand in need of the redemption Christ brings (see Rom. 1:18–3:20; 5:1–7:25). Sin does not merely constitute failure to keep the law of God, but represents personal rebellion against God’s lordship (1 John 3:4). The essence of sin is idolatry, in which people refuse to give thanks and praise to the one and only God, and worship the creature rather than the Creator (Rom. 1:18–25).

But sin is not the last word, since Jesus Christ came to save sinners, thereby highlighting the mercy and grace of God. The fundamental response demanded by God is faith and repentance (see note on Acts 2:38). The call to faith and repentance is evident in the ministry of John the Baptist, in Jesus’ announcement of the kingdom (Mark 1:15), in the speeches in Acts, in the Pauline letters, and throughout the NT. Those who desire to be part of Jesus’ new community (the church) and part of the kingdom of God (God’s rule in people’s hearts and lives) must forsake false gods, renounce self-worship and evil, and turn to Jesus as Lord and Master. The call to repentance is nothing less than a summons to abandonment of sin and to personal faith, whereby people are called to trust in the saving work of the Lord on their behalf instead of thinking that they can save themselves. All people everywhere have violated God’s will and must look outside of themselves to the saving work of Christ for deliverance from God’s wrath. Indeed, the whole of the NT can be understood as a call to repentance and faith (cf. Hebrews 11). Even those who are already believers are to exert themselves in faith and repentance as long as life lasts, for this is the mark of Christ’s true disciples. The NT writers constantly encourage their readers to persevere in faith until the end, and warn of the dangers of rejecting Jesus as Lord at any stage. True believers testify that salvation is of the Lord, and that Jesus Christ is the One who has delivered them from the coming wrath.

The People of God

The saving promises of God, then, have begun to be fulfilled in a new community, the church of Jesus Christ. The church is composed of believers in Jesus Christ, both Jews and Gentiles, for the laws in the OT that separated Jews from Gentiles (e.g., circumcision, purity laws, and special festivals and holidays) are no longer in force. The church is God’s new temple, indwelt by the Holy Spirit, and is called to live out the beauty of the gospel by showing the supreme mark of Christ’s disciples: love for one another (John 13:34–35).

The church recognizes, however, that she exists in an interim state. She eagerly awaits the return of Jesus Christ, and the consummation of all of God’s purposes. In the interim, the church is to live out her life in holiness and godliness as the radiant bride of Christ, and to herald the good news of salvation to the ends of the earth, so that others who live in the darkness of sin may be transferred from Satan’s kingdom to the kingdom of the Lord. The church longs for the day when she will behold God face-to-face and worship Jesus Christ forever. The new creation will be a full reality, all things will be new, and the Lord will be praised forever for his love and mercy and grace—for NT theology is ultimately about glorifying and praising God.