The Canon of Scripture

Share

The Canon of Scripture

The Canon of the Old Testament

The word “canon” (Gk. for “a rule”) is applied to the Bible in two ways: first, in regard to the Bible as the church’s standard of faith and practice, and second, in regard to its contents as the correct collection and list of inspired books. The word was first applied to the identity of the biblical books in the latter part of the fourth century a.d., reflecting the fact that there had recently been a need to settle some Christians’ doubts on the matter. Before this, Christians had referred to the “Old Testament” and “New Testament” as the “Holy Scriptures” and had assumed, rather than made explicit, that they were the correct collections and lists.

The Causes of Uncertainty about the OT Canon

The Christian OT corresponded to the Hebrew Bible, which Jesus and the first Christians inherited from the Jews. In the Gentile mission of the church, however, it was necessary to use the Septuagint (a translation of the OT that had been made in pre-Christian times for Greek-speaking Alexandrian Jews; see The Septuagint). Because knowledge of Hebrew was uncommon in the church (esp. outside Syria and Palestine), the first Latin translation of the OT came from the Septuagint and not from the original Hebrew. Where there was no knowledge of Hebrew and little acquaintance with Jewish tradition, it became harder to distinguish between the biblical books and other popular religious reading matter circulating in the Greek or Latin language. These factors led to the uncertainty about the composition of Scripture, which the coiners of the term “canon” sought to settle.

Did the Hebrew Bible Contain the Same Books as Today’s OT?

The above analysis assumes that the Hebrew Bible, which the church inherited in the first century, comprised the same books as it does today, and that uncertainty developed only later. Many in modern times have denied this view, but for mistaken reasons.

Are the Sections of Scripture Arbitrary Groups, Canonized in Different Eras?

Until recently, the accepted critical view was that the three sections of the Hebrew Bible—the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings (or Hagiographa)—were arbitrary groupings of books acknowledged as canonical in three different eras: the first section in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah (5th century b.c.); the last section at the synod of Jabneh or Jamnia (as late as a.d. 90); and the middle section sometime in between (perhaps in the 3rd century b.c.). The reasons given for the datings were as follows: (1) Because the Samaritans acknowledged only the Pentateuch (the five books of the Law) as Scripture, therefore the Pentateuch must have constituted the whole Jewish canon when the Samaritan schism took place at the time of Ezra and Nehemiah. (2) Because the synod of Jamnia discussed the canonicity of Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, and presumably the other three books with which some rabbis had problems (Ezekiel, Proverbs, and Esther), these must still have been outside the Canon at the time. (3) Chronicles and Daniel, which are found in the Writings section of the Hebrew Bible, would have belonged more naturally with Kings and the oracular Prophets than with the Hagiographa; from this it was concluded that the Prophets section had been closed too soon to include them.

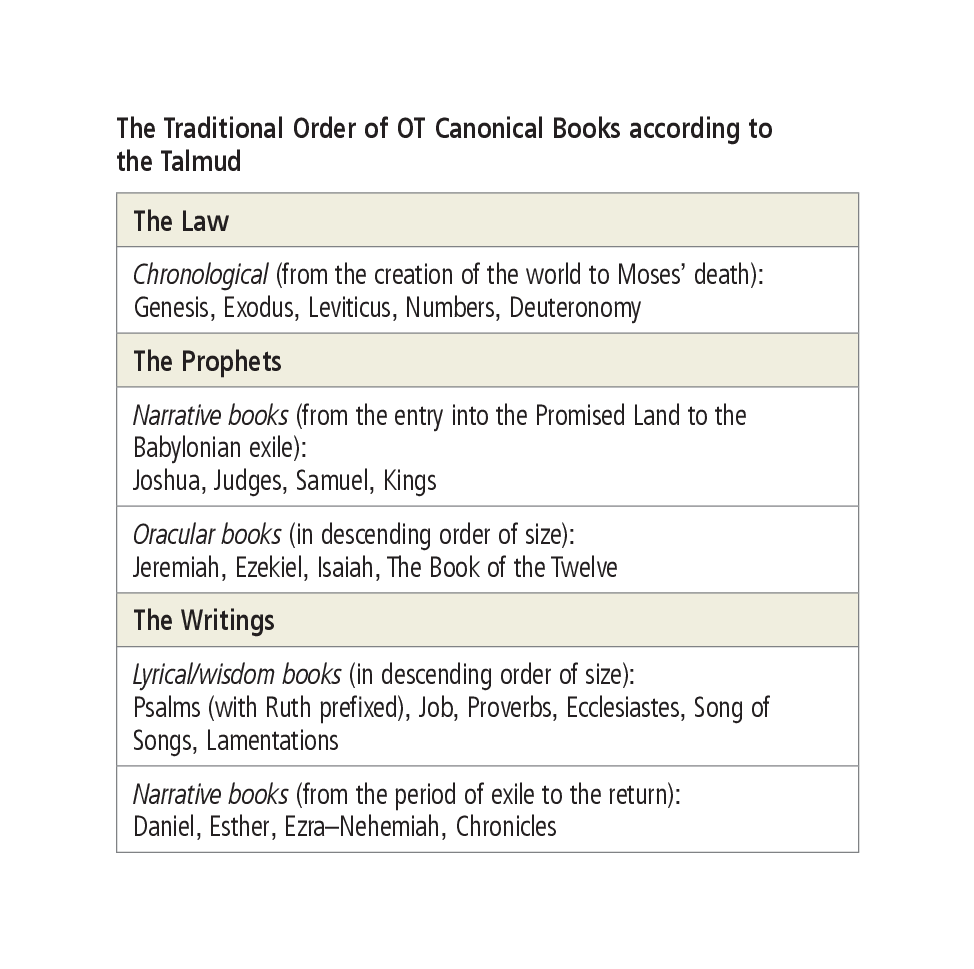

Recent study, however, has demolished this hypothesis. The five books of the Law are obviously not an arbitrary grouping. They follow a chronological sequence, concentrate on the Law of Moses, and trace history from the creation of the world to Moses’ death. Moreover, the Prophets and the Writings, if arranged in the traditional order recorded in the Talmud (see chart), are not arbitrary groupings either. The Prophets begin with four narrative books—Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings—tracing history through a second period, from the entry into the Promised Land to the Babylonian exile. They end with four oracular books—Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah, and the Book of the Twelve (Minor Prophets)—arranged in descending order of size. The Hagiographa (Writings) begin with six lyrical or wisdom books—Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, and Lamentations—arranged in descending order of size, and end with four narrative books—Daniel, Esther, Ezra–Nehemiah, and Chronicles—covering a third period of history, the period of the exile and the return. (The remaining book of the Writings, Ruth, is prefixed to Psalms, since it ends with the genealogy of the psalmist David.) The four narrative books in the Hagiographa are this time put second, so that Chronicles can sum up the whole biblical story, from Adam to the return from exile, and for this reason also Ezra–Nehemiah is put before Chronicles, not after it. A small anomaly is that the Song of Solomon is in fact slightly shorter than Lamentations, not longer, but it is put first to keep the three books related to Solomon together. That Daniel is treated as a narrative book may be surprising, but it is undeniable that it begins with six chapters of narrative.

The Traditional Order of OT Canonical Books according to the Talmud

| The Law |

| Chronological (from the creation of the world to Moses’ death): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy |

| The Prophets |

| Narrative books (from the entry into the Promised Land to the Babylonian exile): Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings |

| Oracular books (in descending order of size): Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah, The Book of the Twelve |

| The Writings |

| Lyrical/wisdom books (in descending order of size): Psalms (with Ruth prefixed), Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Lamentations |

| Narrative books (from the period of exile to the return): Daniel, Esther, Ezra–Nehemiah, Chronicles |

Each of the three sections of the OT canon has a narrative component, covering one of three successive periods of history, and a literary component, representing one of three different types of religious literature: law, oracles, and lyrics or wisdom. The narrative material is, as far as possible, arranged in chronological order, and the literary material, when not united with the narrative material (as in the Pentateuch), is arranged in descending order of size. The shape of the Canon is therefore no accident of history but a work of art, and in its final form must be due to a single thinker, living before c. 130 b.c., when the three sections are first mentioned in the Greek prologue to Sirach (in the Apocrypha).

The datings assigned to the recognition of the three sections are also misconceived. First, it is now known that the Samaritans continued to follow Jewish customs long after the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, and that the schism did not become complete until the Jews destroyed the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim in about 110 b.c. It seems that the Samaritans only then rejected the Prophets and Writings because of the recognition those books give to the temple at Jerusalem.

Second, the problems that some rabbis had with as many as five biblical books do not mean that those books were outside the Canon, since the rabbinical literature notes similar problems with many other biblical books, including all five books of the Pentateuch. The problems with the five disputed books may have been particularly difficult, but they, too, were eventually solved in the same way as the other problems. There was no “synod of Jamnia” but simply a discussion at its academy that confirmed the canonicity of Ecclesiastes and the Song of Solomon—though that discussion did not end the controversy. Esther, in particular, continued to be discussed long after a.d. 90. Further, the same kinds of questions were raised about Ezekiel, which is found in the Prophets, not in the Writings; if the reasoning of the critical view were sound, then the Prophets also could not have been in the Canon, which would be absurd.

Third, contrary to what the critical view suggested, there would have been no strong incentive to put Chronicles and Daniel in the Prophets, since they were both being treated as narrative books relating to the final period of OT history and therefore belonging in the Hagiographa.

Was There a Distinct Alexandrian Canon?

A further fallacious argument that many critics have used to show that the OT canon was still open at the beginning of the Christian era is the hypothesis of a distinct Alexandrian canon, including at least some of the apocryphal books. For discussion of this argument, see the discussion of “How the Greek and Latin Translations Came to Contain the Apocrypha,” in The Apocrypha.

Did the Qumran Sect Have a Broader OT Canon?

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran has turned the attention of critics to the pseudepigrapha—notably 1 Enoch, The Testament of Levi, Jubilees, and The Temple Scroll. It is today frequently claimed that the men of Qumran (probably Essenes) had a broad canon that included these books. But it should be noted that (1) the pseudonyms used in these works belong to the biblical period, indicating a recognition that prophetic inspiration had now ceased; (2) the inspiration claimed at Qumran was an inspiration to interpret the Scriptures, not to add to them; (3) the quotations from authoritative works made in the Qumran writings are almost exclusively from the OT books, and the formulas used for quoting Scripture are not used with the few quotations from elsewhere; and (4) though the Essenes may have added an interpretative appendix to the three standard sections of the OT canon, containing their favored pseudepigrapha, it is significant that they did not try to insert them into the three standard sections, which were now evidently closed (i.e., seen as complete).

The Truth about the OT Canon

So much for fashionable errors regarding the assembling and recognition of the OT canon. The true evidence of the process is comparatively simple. First, it was recognized from ancient times that, if revelation was to be preserved, it needed to be written down (see Ex. 17:14; Deut. 31:24–26; Ps. 102:18; Isa. 30:8). This process of writing the words had been begun by God himself at Mount Sinai, when he gave Moses the two tablets of stone with his own words written on them: “The tablets were the work of God, and the writing was the writing of God, engraved on the tablets” (Ex. 32:16). These tablets were deposited in the ark of the covenant (Deut. 10:5) and were the basis of the covenant relationship between God and his people. Then, later writings were added to “the Book of the Covenant” (see Ex. 24:7; Josh. 24:26; 2 Kings 23:2). A significant object lesson on the importance of preserving God’s words in written form was the later discovery of the Book of the Law by Hilkiah, after it had been lost during the reigns of Manasseh and Amon: its teaching came as a great shock because it had been forgotten (2 Kings 22–23; 2 Chronicles 34).

Second, on great national occasions the Book of the Law was read to the people (Ex. 24:7; 2 Kings 23:2; Neh. 8:9, 14–17, etc.). Deuteronomy provides for it to be read regularly every seven years (Deut. 31:10–13). An extension of the same practice was the later reading of the Pentateuch in the synagogue on the Sabbath, supplemented by a reading from the Prophets (Luke 4:16–20; Acts 13:15, 27; 15:21, etc.).

Third, Deuteronomy was to be laid up in the sanctuary (Deut. 31:24–26), and that was where Hilkiah found the Book of the Law (2 Kings 22:8; 2 Chron. 34:15). It is known from Josephus and the earliest rabbinical literature that the practice of laying up the Scriptures in the temple still continued down to the first century a.d. To lay up any book there as Scripture must have been a solemn and carefully deliberated act of national significance.

Fourth, the calendar of the book of 1 Enoch, followed at Qumran, seems to have been devised in about the third century b.c. so as to avoid having any dated act recorded in the Scriptures occur on the Sabbath. At least 10 (and probably more) of the present OT books are shown to be acknowledged as canonical at this time by this listing.

Fifth, Sirach 44–49, written about 180 b.c., provides a catalog of famous men, and these are probably all meant to be biblical figures, since they are all now found in the Bible. The end of Sirach 49 sums them up, while chapter 50 moves on to describe Simon the son of Onias, a later worthy figure not found in the Bible. Accounting for these men raises the number of books to at least 16 for which there is specific extrabiblical attestation to canonicity.

Sixth, Josephus relates that the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes first became distinct and rival schools of thought in the time of Jonathan Maccabeus (d. 143 b.c.). To alter the Canon after this time would have been very controversial, and can hardly have occurred. So the Canon must have been acknowledged as closed before 143 b.c.

Seventh, the final touches may have been put to the Canon in 165 b.c. by Judas Maccabeus (making it a listed collection of 24 books in three sections, beginning with Genesis and ending with Chronicles; see chart), when he gathered the scattered Scriptures after Antiochus’s persecution (2 Macc. 2:14). This is the Bible that, two centuries later, the NT and other first-century writings reflect.

Eighth, in spite of numerous differences between Jesus and the Jewish religious leaders of his time, there is no record of any dispute between them, or any later dispute with Jesus’ apostles, over which OT books were canonical. The OT canon accepted by the early church was identical to the canon of books accepted by the Jewish people.

Ninth, Jesus and the NT authors quote the words of the OT approximately 300 times (see Old Testament Passages Cited in the New Testament; uncertainty about the exact number arises because of a few instances where it is not clear whether it is an OT quotation or only an echoing expression using similar words). They regularly quote it as having divine authority, with phrases such as “it is written,” “Scripture says,” and “God says,” but no other writings are quoted in this way. Occasionally the NT writers will quote some other authors, even pagan Greek authors, but they never quote these other sources as being the words of God (see notes on Acts 17:28; Titus 1:12–13; Jude 8–10, 14–16), as they do the canonical OT books.

Tenth, Josephus (born a.d. 37/38) explained, “From Artaxerxes to our own times a complete history has been written, but has not been deemed worthy of equal credit with the earlier record, because of the failure of the exact succession of the prophets” (Against Apion 1.41). Josephus was aware of the writings now considered part of the Apocrypha, but he (and, he implies, mainstream Jewish opinion) considered these other writings “not . . . worthy of equal credit” with what are now known as the OT Scriptures.

Eleventh, additional Jewish tradition after the time of the NT also expresses the conviction that no more prophetic writings had been given after the time of the last OT prophets Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi (see Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 9b; Sotah 48b; Sanhedrin 11a; and Midrash Rabbah on Song of Songs 8.9.3).

Sound historical study shows, therefore, that the Hebrew OT contains the true canon of the OT, shared by Jesus and the apostles with first-century Judaism. No books are left out that should be included, and none are included that should be left out.

The Canon of the New Testament

The foundations for a NT canon lie not, as some would assert, in the needs or the practices of the church in the second, third, and fourth centuries a.d., but in the gracious purpose of a self-revealing God whose word carries his own divine authority. Just as new outpourings of divine word-revelation accompanied and followed each major act of redemption in the ancient history of God’s people (the covenant with Adam and Eve, the covenant with Abraham, the redemption from Egypt, the establishment of the monarchy, the exile, and the restoration), so when the promised Messiah came, a new and generous outpouring of divine revelation necessarily ensued (see 2 Tim. 1:8–11; Titus 1:1–3).

The OT Authorization

The prospect of a NT Scripture to stand alongside the OT was anticipated, even authorized, in the OT itself, embedded in the promise of God’s ultimate act of redemption through the Messiah, in faithfulness to his covenant (Jer. 31:31–33; cf. Heb. 8:7–13; 10:16–18). Jesus taught his disciples after his resurrection that “the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms” predicted not only the Messiah’s suffering and resurrection but also that “repentance and forgiveness of sins should be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem” (Luke 24:44–48). Prophetic passages such as Isaiah 2:2–3; 49:6; and Psalm 2:8 spoke of a time when the light of God’s grace in redemption would be proclaimed to all nations. It naturally follows that this proclamation would eventuate in a new collection of written Scriptures complementing the books of the old covenant—both from the pattern of God’s redemptive work in the past (mentioned above) and from the actual writing ministry of some of Jesus’ apostles (and their associates) in the accomplishment of their commission.

The Commission of Jesus

God, who spoke in many and various ways in times past, chose to speak in these last days to mankind through his Son (see Heb. 1:1–2, 4). Bringing this saving message to Israel and the nations was a crucial part of the mission of Jesus Christ (Isa. 49:6; Acts 26:23), the Word made flesh (John 1:14). He put this mission into effect through chosen apostles, whom he commissioned to be his authoritative representatives (Matt. 10:40, “whoever receives you receives me”). Their assignment was to “bring to . . . remembrance,” through the work of the Spirit, his words and works (John 14:26; 16:13–14) and to bear witness to Jesus “in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8; cf. Matt. 28:19–20; Luke 24:48; John 17:14, 20). In time, the apostolic preaching came to written form in the books of the NT, which now function as “the commandment of the Lord and Savior through your apostles” (2 Pet. 3:2).

Paul and the other apostles wrote just as they preached: conscious of Jesus’ mandate. From the beginning, the full authority of the apostles (and prophets) to deliver God’s word was recognized, at least by many (Acts 10:22; Eph. 2:20; 1 Thess. 2:13; Jude 17–18). This recognition is accordingly reflected in the earliest non-apostolic writers. For example, Clement of Rome attested that “The apostles received the gospel for us from the Lord Jesus Christ; Jesus the Christ was sent forth from God. So then Christ is from God, and the apostles are from Christ. Both, therefore, came of the will of God in good order” (1 Clement 42.1–2 written c. a.d. 95).

The Recognition of New Covenant Scriptures

As God’s word to mankind, the “God-breathed” Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16) is self-attesting, and thus the Canon may be said to be self-establishing. Yet history records that for centuries there were variations in local church practice and disagreements among churches and early theologians about several books of the NT. Such variations, however, are not unexpected, given that the process of recognition involved more than two dozen books that came into being over a period of perhaps 50 years, circulating unsystematically to churches as they were springing up in widely diffused parts of the Roman Empire.

In its deliberations about the particular books that make up the canon of Scripture, the church did not sovereignly “determine” or “choose” the books it most preferred—whether for catechetical, polemical, liturgical, or edificatory purposes. Rather, the church saw itself as empowered only to receive and recognize what God had provided in books handed down from the apostles and their immediate companions (e.g., Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.preface; 3.1.1–2). This is why discussions of the so-called “criteria” of canonicity can be misleading. Qualities such as “apostolicity,” “antiquity,” “orthodoxy,” “liturgical use,” and “church consensus” are not criteria by which the church autonomously judged which documents it would receive. The first three are qualities the church recognizes in the voice of its Savior, to which voice the church willingly submits itself (“My sheep hear my voice . . . and they follow me,” John 10:27).

The Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (the earliest Gospels known) gained universal acceptance while arousing very little controversy within the church. If the latest of these, the Gospel of John, was published near the end of the first century (as most scholars think), it is remarkable that its words are echoed around a.d. 110 in the writings of Ignatius of Antioch, who also knew Matthew, and perhaps Luke. At about the same time, Papias of Hierapolis in Asia Minor received traditions about the origins of Matthew’s and Mark’s Gospels, and quite probably Luke’s and John’s. In the middle of the second century, Justin Martyr in Rome reported that the Gospels (apparently the four)—which he calls “memoirs of the apostles”—were being read and exposited in Christian services of worship.

In 2 Peter 3:16, a collection of at least some of Paul’s letters was already known and regarded as Scripture and therefore enjoyed canonical endorsement. Furthermore, a collection (of unknown extent) of Paul’s letters was known to Clement of Rome and to the recipients of his letter in Corinth before the end of the first century, then also to Ignatius of Antioch and Polycarp of Smyrna and their readers in the early second century. The Pastoral Letters (1–2 Timothy and Titus), rejected as Paul’s by many modern critics, are attested at least from the time of Polycarp.

By the end of the second century a “core” collection of NT books—21 of the 27—was generally recognized: four Gospels, Acts, 13 epistles of Paul, 1 Peter, 1 John, and Revelation. By this time Hebrews (accepted in the East and by Irenaeus and Tertullian in the West, but questioned in Rome due to doubts about authorship), James, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and Jude were only minimally attested in the writings of church leaders. This infrequent citation led to the expression of doubts by later fathers (e.g., Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.23.25). Yet, by some time in the third century, codices (precursors of the modern book form, as opposed to scrolls) containing all seven of the “general epistles” were being produced, and Eusebius reports that all seven were “known to most.”

An unusual case is the book of Revelation, which seems to have been accepted everywhere at first (in the West by Justin, Irenaeus, the Muratorian Fragment, and Tertullian; in the East by Clement of Alexandria and Origen). But due to its exploitation by Montanists and others, it was criticized by Gaius, a Roman writer in the early third century. Several decades later, Dionysius of Alexandria, while not rejecting the book, argued that it could not have been written by the apostle John. These factors led to enduring doubts in the East and to Revelation’s absence from later Eastern canon lists, though its reputation in the West did not suffer.

To complicate matters, many documents were produced in the course of the second century which in some way paralleled or imitated NT books. Many of these made some claim to apostolic authority, and some gained considerable popularity in certain quarters. One or more “Gospels” written in Aramaic attracted interest because of a presumed connection to an original Aramaic Matthew. Other “Gospels” were essentially combinations of the four (i.e., The Gospel of Peter and The Egerton Gospel), a practice that culminated in Tatian’s Diatessaron, a harmony of the four (c. a.d. 172), which was the first form of the Gospels translated into Syriac.

There was a profusion of “Acts” literature, usually following, in novel-like fashion, the fictional exploits of a single apostle (Paul, John, Andrew, Peter). Letters forged in the name of Paul (To the Laodiceans, To the Alexandrians, 3 Corinthians) sought to attract adherents to an assortment of special causes. Works in various genres written to advance unorthodox interpretations of Christianity often borrowed the names of apostles (Apocryphon of John, Gospel of Thomas). In addition, a few writings, probably never intended to be regarded as Scripture, were honored as such by some Christians partly because of assumed authorship by companions of apostles (1 and 2 Clement, The Letter of Barnabas, The Shepherd of Hermas).

By the 240s a.d. Origen (residing in Caesarea in Palestine) acknowledged all 27 of the NT books but reported that James, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and Jude were disputed. The situation is virtually the same for Eusebius, writing about 60 years later, who also reports the doubts some had about Hebrews and Revelation. Still, his two categories of “undisputed” and “disputed but known to most” contain only the 27 and no more. He named five other books (The Acts of Paul, The Shepherd of Hermas, The Apocalypse of Peter, The Letter of Barnabas, and The Didache) which were known to many churches but which, he believed, had to be judged as spurious.

In the year a.d. 367 the Alexandrian bishop Athanasius, in his annual Easter letter, gave a list of the NT books which comprised, with no reservations, all 27, while naming several others as useful for catechizing but not as scriptural. Several other fourth-century lists essentially concurred, though with various individual deviations outside of the most basic core (four Gospels, Acts, 13 epistles of Paul, 1 Peter, 1 John). Three African synods—at Hippo Regius in a.d. 393 and at Carthage in 397 and 419—and the influential African bishop Augustine affirmed the 27-book Canon. It was enshrined in Jerome’s Latin translation, the Vulgate, which became the normative Bible for the Western church. In Eastern churches, recognition of Revelation lagged for quite some time. The churches of Syria did not accept Revelation, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, or Jude until the fifth (Western Syria) or sixth (Eastern Syria) centuries.

The apostolic word gave birth to the church (Rom. 1:15–17; 10:14–15; James 1:18; 1 Pet. 1:23–25), and the written form of this word remains as the permanent, documentary expression of God’s new covenant. It may be said that only the 27 books of the NT manifest themselves as belonging to that original, foundational, apostolic witness. They have demonstrated themselves to be the Word of God to the universal church throughout the generations. Here are the pastures to which Christ’s sheep from many folds continually come to hear their Shepherd’s voice and to follow him.

The Apocrypha

Larger editions of the English Bible—from the Great Bible of Tyndale and Coverdale (1539) onward—have often included a separate section between the OT and the NT titled “The Apocrypha,” consisting of additional books and substantial parts of books. The Latin Vulgate Bible translated by Jerome (begun a.d. 382, completed 405) had placed them in the OT itself—some as separate items and some as attached to or included in the biblical books of Esther, Jeremiah, and Daniel. In Roman Catholic translations of the Bible, such as the Douay Version and the Jerusalem Bible, these items are still placed in their pre-Reformation positions. In Protestant translations, however, the Apocrypha is either omitted altogether or grouped in a separate section.

How Jerome’s Vulgate Came to Contain the Apocrypha

In distinguishing the Apocrypha from the OT books, the Protestant translators were not doing something completely novel but were carrying out more thoroughly than ever before the principles on which Jerome (a.d. 345–420) had made his great Latin Vulgate translation of the OT. The Vulgate was translated from the original Hebrew. But a translation prior to the Vulgate, the Old Latin translation, had been made from the Greek OT, the Septuagint (or lxx). At some stage, early or late, additional books and parts of books, which were not in the Hebrew Bible, had found their way into the Greek OT, and from there into the Old Latin version. Jerome retained these in his new translation, the Latin Vulgate, but added prefaces at various points to emphasize that they were not true parts of the Bible, and he called them by the name “apocrypha” (Gk. apokrypha, “those having been hidden away”). In accordance with his teaching—and with the understanding of the OT canon held by Jesus, the NT authors, and the first-century Jews (see The Canon of the Old Testament)—the sixteenth-century Protestant translators did not consider those writings part of the OT but gathered them together in a separate section, to which they gave Jerome’s name, “The Apocrypha.”

Jerome’s reason for choosing this name is not readily apparent. He probably took a hint from Origen, who a century and a half earlier had stated that the Jews applied this name to the most esteemed of their noncanonical books. Origen and Jerome were two of the most distinguished students of Judaism among the Fathers, so it would be natural for them to use the term in a Jewish sense, though applying it to the noncanonical Jewish books that were most esteemed by Christians. Jews would never destroy respected religious books but, if unfit for use, hid them away and left them to decay naturally. So “hidden” came to mean “highly esteemed, though uncanonical.”

Jerome did not actually confine his name “apocrypha” to Jewish books but used it also of noncanonical Christian books, such as The Shepherd of Hermas, which were likewise popular religious reading among Christians. The modern expression “New Testament Apocrypha,” for late works that imitate NT literature, is similar.

How the Greek and Latin Translations Came to Contain the Apocrypha

How the Greek OT, and by consequence the Latin OT, came to contain apocryphal items has been variously understood. Codex Alexandrinus (the great 5th-century a.d. manuscript of the whole Greek Bible) was printed and published in the eighteenth century. Because it contained the Apocrypha, the editors in the eighteenth century assumed that the OT of this Christian manuscript had been copied from Jewish manuscripts equally inclusive, and that consequently the Apocrypha must have been in the lxx translation, and in the canon of the Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria who produced it from pre-Christian times (though not in the Bible or canon of the Semitic-speaking Jews of Palestine). This hypothesis held the field for a long time, and a further assumption—that most of the apocryphal books had been composed in Greek, outside Palestine—was made to support it.

All the elements of this theory are now known to be false. (1) Leather manuscripts large enough to contain the whole OT did not exist among either Christians or Jews until the latter part of the fourth century. The earlier Christian biblical manuscripts are on papyrus, and extend only to about three of the larger books. (2) The Jews of Alexandria took their lead largely from Palestine, and would have been unlikely to establish their own distinct canon; moreover, their greatest writer, Philo, though frequently quoting from the OT in his voluminous works, never refers to any of the Apocrypha whatsoever. (3) The earliest Christian biblical manuscripts contain the fewest books of the Apocrypha, and up until a.d. 313, only Wisdom, Tobit, and Sirach ever occur in them; other books of the Apocrypha were not added until later. (4) That the Apocrypha was mostly composed in Greek or outside Palestine is no longer widely believed, and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) itself states that it was composed in Hebrew (see its prologue; much of its Hebrew text has now been recovered). All the Apocrypha except Wisdom and 2 Maccabees may in fact have been translated from a Hebrew or Aramaic original, written in Palestine.

The way in which Christian writers used the Apocrypha confirms the above analysis. The NT seems to reflect knowledge of one or two of the apocryphal texts, but it never ascribes authority to them as it does to many of the canonical OT books. While the NT quotes various parts of the OT about 300 times (see Old Testament Passages Cited in the New Testament), it never actually quotes anything from the Apocrypha (Jude 14–16 does not contain a quote from the Apocrypha but from another Jewish writing, 1 Enoch; see note on Jude 14–16; also notes on Acts 17:28; Titus 1:12–13; Jude 8–10). In the second century, Justin Martyr and Theophilus of Antioch, who frequently referred to the OT, never referred to any of the Apocrypha. By the end of the second century Wisdom, Tobit, and Sirach were sometimes being treated as Scripture, but none of the other apocryphal books were. Their eventual acceptance was a slow development. Much the same is true with Christian lists of the OT books: the oldest of them include the fewest of the Apocrypha; and the oldest of all, that of Melito (c. a.d. 170), includes none.

Acceptance and Rejection of the Apocrypha

The growing willingness of the pre-Reformation church to treat the Apocrypha as not just edifying reading but Scripture itself reflected the fact that Christians—especially those living outside Semitic-speaking countries—were losing contact with Jewish tradition. Within those countries, however, a learned Christian tradition akin to elements of Jewish tradition was maintained, especially by scholars such as Origen, Epiphanius, and Jerome, who cultivated the Hebrew language and Jewish studies. By the late fourth century, Jerome found it necessary to assert the distinction between the Apocrypha and the inspired OT books with great emphasis, and a minority of writers continued to make the same distinction throughout the Middle Ages, until the Protestant Reformers arose and made the distinction an important part of their doctrine of Scripture. At the Council of Trent (1545–1563), however, the church of Rome attempted to obliterate the distinction and to put the Apocrypha (with the exception of 1 and 2 Esdras and The Prayer of Manasseh) on the same level as the inspired OT books. This was a consequence of (1) Rome’s exalted doctrine of oral tradition, (2) its view that the church creates Scripture, and (3) its acceptance of certain controversial ideas (esp. the doctrines of purgatory, indulgences, and works-righteousness as contributing to justification) that were derived from passages in the Apocrypha. These teachings gave support to the Roman Catholic responses to Martin Luther and other leaders of the Protestant Reformation, which had begun in 1517.

Because of these controversial passages, some Protestants ceased to use the Apocrypha altogether. But other Protestants (notably Lutherans and Anglicans), while avoiding such passages and the ideas they contain, continued to read the Apocrypha as generally edifying religious literature. The Apocrypha, together with other postcanonical literature (esp. the pseudepigrapha, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the writings of Philo and Josephus, the Targums, and the earliest rabbinical literature) can be helpful in additional ways. They provide the earliest interpretations of the OT literature; they explain what happened in the time between the two Testaments; and they introduce customs, ideas, and expressions that provide a helpful background when reading the NT.

The Contents of the Apocrypha

Individually, the books of the Apocrypha are 15 in number (but some count 14 or 12 by combining some books; see list) and consist of various kinds of literature—narrative, proverbial, prophetic, and liturgical. They probably range in date from the third century b.c. (Tobit) to the first century a.d. (2 Esdras and perhaps The Prayer of Manasseh).

1. First Esdras (Gk. for “Ezra”), sometimes called 3 Esdras, covers the same ground as the book of Ezra, with a little of Chronicles and Nehemiah added. It also relates a debate on “the strongest thing in the world.”

2. Second Esdras, sometimes called 4 Esdras, is a pseudonymous apocalypse, preserved in Latin, not Greek, with two Christian chapters added at the beginning and two at the end. Chapter 14 gives the number of the OT books. First and Second Esdras are not included in the Roman Catholic canon.

3. Tobit is a moral tale with a Persian background, dealing with almsgiving, marriage, and the burial of the dead.

4. Judith is an exciting story, in a confused historical setting, about a pious and patriotic heroine.

5. The Additions to Esther are a collection of passages added to the lxx version of Esther, bringing out its religious character.

6. Wisdom is a work inspired by Proverbs and written in the person of Solomon.

7. Sirach, also called Ecclesiasticus, is a work somewhat similar to Wisdom, by a named author (Jeshua ben Sira, or Jesus the son of Sirach). It was written about 180 b.c., and its catalog of famous men bears important witness to the contents of the OT canon at that date. Its translator’s prologue, written half a century later, refers repeatedly to the three sections of the Hebrew Bible (see The Canon of the Old Testament.)

8. Baruch is written in the person of Jeremiah’s companion, and somewhat in Jeremiah’s manner.

9. The Epistle of Jeremiah is connected to Baruch, and sometimes the two are counted together as one book (as in the kjv, which therefore lists 14 books rather than 15).

The Additions to Daniel consist of three segments (10, 11, and 12 in this list):

10. Susanna and

11. Bel and the Dragon are stories that tell how wise Daniel exposed unjust judges and deceitful pagan priests.

12. The Song of the Three Young Men contains a prayer and hymn put into the mouths of Daniel’s three companions when they are in the fiery furnace; the hymn is the one used in Christian worship as the Benedicite (in the Church of England’s services).

As stated before, some authorities count these three books (items 10, 11, and 12) as one book, namely, The Additions to Daniel, and they also count Baruch as one book that includes The Epistle of Jeremiah; in that way, they count only 12 books in the Apocrypha.

13. The Prayer of Manasseh puts into words Manasseh’s prayer for forgiveness in 2 Chronicles 33:12–13. It is not included in the Roman Catholic canon.

14–15. First and Second Maccabees relate the successful revolt of the Maccabees against the Hellenistic Syrian persecutor Antiochus Epiphanes in the mid-second century b.c. The first book and parts of the second book are the primary historical sources for a knowledge of the Maccabees’ heroic faith, though the second book adds legendary material. The lxx also contains a 3 and 4 Maccabees, but these are of less importance.

The Development of Religious Thought in the Apocrypha

The development of religious thought found in the Apocrypha, going beyond the teaching of the OT, must be assessed by the teaching of the NT. For example, Wisdom 4:7–5:16 teaches that all face a personal judgment after this life. This is consistent with later NT teaching (Heb. 9:27).

Other teachings add doctrinal material foreign to NT teaching, such as the following:

1. In Tobit 12:15 seven angels are said to stand before God and present the prayers of the saints.

2. In 2 Maccabees 15:13–14 a departed prophet is said to pray for God’s people on earth.

3. In Wisdom 8:19–20 and Sirach 1:14 the reader is told that the righteous are those who were given good souls at birth.

4. In Tobit 12:9 and Sirach 3:3 readers are told that their good deeds atone for their evil deeds.

5. In 2 Maccabees 12:40–45 the reader is told to pray for the sins of the dead to be forgiven.

The first two ideas find no support in the OT or NT, and the second may be thought to give some support to the Roman Catholic idea of prayer to the saints who have died. The last three tenets are clearly at variance with what the NT teaches about regeneration, justification, and the present life as one’s only period of probation.

The Apocrypha, consequently, must be read with discretion. Though much in it simply reflects Judaism as practiced at a date somewhat later than the OT, and some parts reflect developments in the direction of the NT, there are also certain misleading passages that have historical interest but, in terms of Christian theology and practice, are to be avoided.