Reading the Epistles

Share

Reading the Epistles

Introduction and Timeline

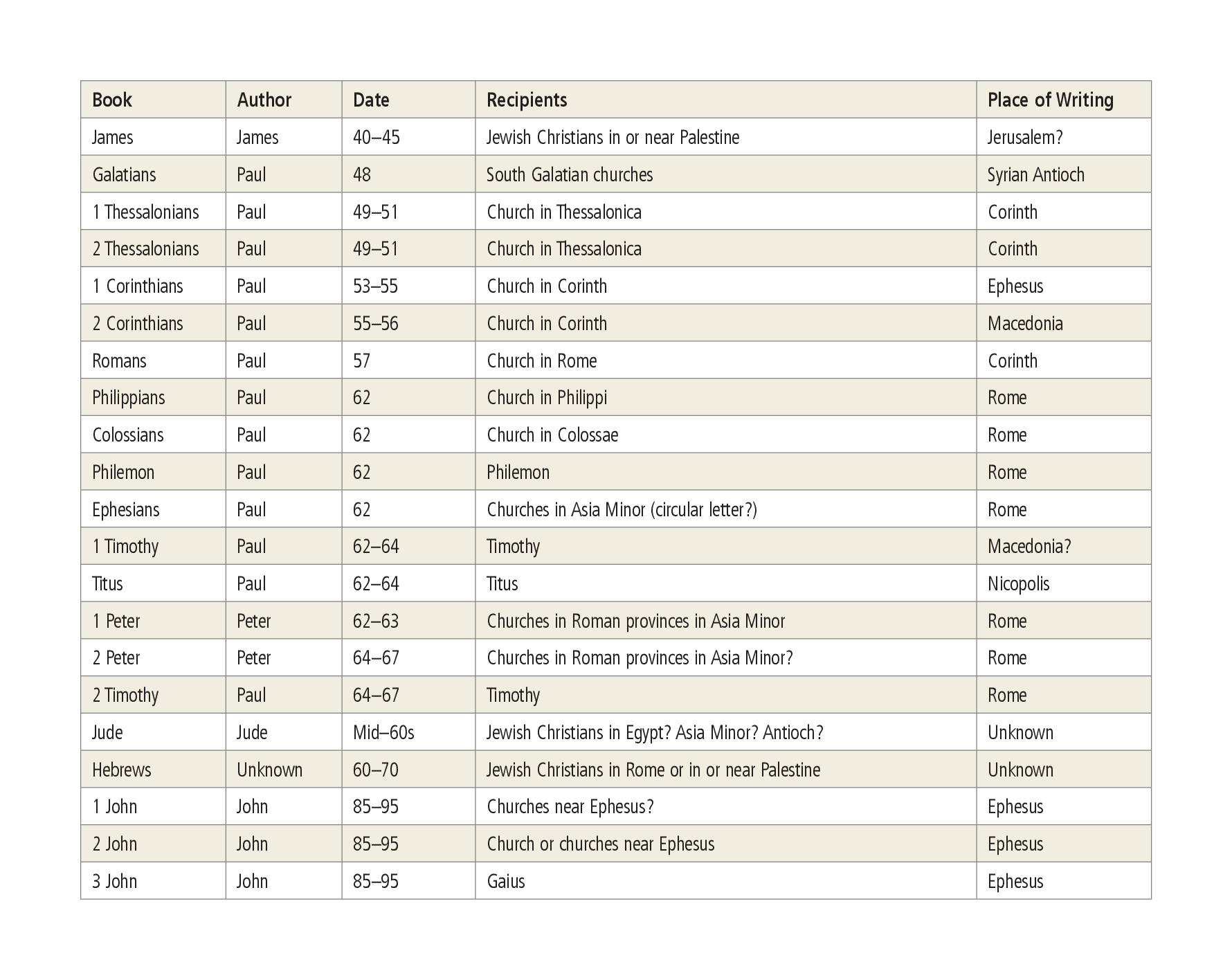

Knowing how to read the Epistles is very important, since they make up 21 of the 27 books in the NT. Paul wrote 13 of them. Three were written by the apostle John, two by Peter, one each by James and Jude (the brothers of Jesus), and one by the unknown author of Hebrews. Ascertaining the dates of the Epistles, their places of origin, and the recipients is in some instances quite difficult because, unlike modern books, a date is never included, the recipients are not always mentioned, and the place where the letters were written is not stated. In most cases, though, we can be fairly confident of an approximate date, and the recipients are often explicitly named. We suggest for the Epistles the information shown in the chart (all dates are a.d. and approximate).

| Book | Author | Date | Recipients | Place of Writing |

| James | James | 40–45 | Jewish Christians in or near Palestine | Jerusalem? |

| Galatians | Paul | 48 | South Galatian churches | Syrian Antioch |

| 1 Thessalonians | Paul | 49–51 | Church in Thessalonica | Corinth |

| 2 Thessalonians | Paul | 49–51 | Church in Thessalonica | Corinth |

| 1 Corinthians | Paul | 53–55 | Church in Corinth | Ephesus |

| 2 Corinthians | Paul | 55–56 | Church in Corinth | Macedonia |

| Romans | Paul | 57 | Church in Rome | Corinth |

| Philippians | Paul | 62 | Church in Philippi | Rome |

| Colossians | Paul | 62 | Church in Colossae | Rome |

| Philemon | Paul | 62 | Philemon | Rome |

| Ephesians | Paul | 62 | Churches in Asia Minor (circular letter?) | Rome |

| 1 Timothy | Paul | 62–64 | Timothy | Macedonia? |

| Titus | Paul | 62–64 | Titus | Nicopolis |

| 1 Peter | Peter | 62–63 | Churches in Roman provinces in Asia Minor | Rome |

| 2 Peter | Peter | 64–67 | Churches in Roman provinces in Asia Minor? | Rome |

| 2 Timothy | Paul | 64–67 | Timothy | Rome |

| Jude | Jude | Mid–60s | Jewish Christians in Egypt? Asia Minor? Antioch? | Unknown |

| Hebrews | Unknown | 60–70 | Jewish Christians in Rome or in or near Palestine | Unknown |

| 1 John | John | 85–95 | Churches near Ephesus? | Ephesus |

| 2 John | John | 85–95 | Church or churches near Ephesus | Ephesus |

| 3 John | John | 85–95 | Gaius | Ephesus |

Unity

Most of these letters have three parts: (1) the opening; (2) the body; and (3) the closing. The opening of a letter has four different elements: (1) the sender (e.g., Paul); (2) the recipients (e.g., the Corinthians); (3) the salutation (e.g., “grace and peace to you”); and (4) a prayer (usually a thanksgiving). Not all the letters follow this pattern. The sender is not named in Hebrews, nor are the recipients. The author of 1 John never identifies himself, nor does he specifically address the readers. Indeed, there is no salutation or prayer in Hebrews or 1 John; both launch immediately into the content of the letter.

The body of the letter, which is the longest section in all the letters, does not follow any particular pattern. Here we need to trace out the flow of thought in each letter carefully. The Pauline letters and Hebrews are marked by careful logical progression, while 1 John repeatedly circles back to the same themes and James writes in a style that is reminiscent of wisdom literature such as Proverbs, a collection of shorter teachings on many topics but with no clear overall structure.

The closings in letters vary considerably. Paul often includes travel plans, commendation of coworkers, prayer, prayer requests, greetings, final instructions, an autographed greeting, and a grace benediction.

Although critical scholars have often argued that many of the letters are composites, being stitched together from a variety of different letters, scholars now generally affirm the unity of the letters and have noted their careful structure and the artistry of their unified composition. It is helpful, therefore, to compose a detailed outline as we study the letters, so that as readers we are able to trace the flow of the argument. By doing this we gain a greater understanding of each letter as a whole, since we are prone to read small sections without having a clear map of the entire document. Moreover, having a good understanding of the entirety of the letter assists significantly in interpretation. Often one part of the letter (e.g., the closing) casts light on other parts.

Themes

The Epistles are distinguished from the Gospels in that they are not narrative compositions. In terms of redemptive history, they are written on the other side of the cross and resurrection, so that they typically reflect more deeply on the significance of Christ’s death and resurrection than the Gospels do. The implications of the fulfillment of God’s promises in Jesus Christ are explored and applied to the readers in the Epistles. These same themes are present in the Gospels, of course, but they are not set forth in the same fullness, since the nature of Jesus’ messianic mission often perplexed his disciples during his earthly ministry, and they grasped these realities in their fullness (though still not exhaustively!) only after the cross and resurrection and with the outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost. The Epistles have played a major role in the formation of doctrine and Christian theology throughout church history precisely because they expound on the great themes of God’s saving work on the cross. Because they reflect on and explain the fulfillment of God’s promises in light of the OT and the Gospels, it is particularly fruitful to study their use of the OT, OT allusions, and citations of and allusions to Jesus’ teachings. By doing this we understand more clearly how epistolary writers understood the fulfillment of God’s promises in Christ. We also perceive how they related the OT and the gospel traditions to the churches, and such an understanding assists us in applying not only the Epistles but also the OT and the Gospels to today’s world.

Among the major themes in the Epistles are the following: (1) Jesus Christ is the fulfillment of God’s promises in redemptive history. He is Messiah, Lord, the Son of God, and the true revelation of God. (2) The new life of believers is a gift of God, anchored in the cross and empowered by the Holy Spirit. (3) Christians experience salvation by faith, and faith expresses itself in a transformed life. The Epistles spend considerable space elaborating on believers’ newness of life. (4) Believers belong to the restored Israel, the church of Jesus Christ, which must live out her calling as God’s people in a sinful world. (5) In this present evil age believers suffer affliction and persecution, but they look forward with joy to the coming of Jesus Christ and the consummation of their salvation. (6) False teachers dangerously subvert the true gospel of Christ.

The Circumstances behind the Letters

The Epistles are not abstract philosophical or theological essays that explain the salvation accomplished by Jesus Christ. In almost every instance, they are addressed to specific situations facing churches. It is clear in reading Galatians, Colossians, 2 Peter, and Jude that the letters were written because false teaching had infiltrated the churches. Upon reading 1–2 Corinthians, we realize that Paul wrote in response to various problems in the Corinthian church. The letters are crafted to speak to readers as they face everyday life. In his first letter, Peter addresses readers who were suffering discrimination and persecution. Colossians responds to some kind of mystical teaching that promises readers fullness of life apart from, or going beyond, Christ. Philippians hints that the church suffered from some type of dissension and lack of unity. In the two Thessalonian letters, the church was confused about eschatology, and some believers were apparently becoming lax and failing to work hard. While many themes in Paul’s thought are set forth in Romans, even that letter does not represent a comprehensive exposition of the gospel, for we do not find in the letter a developed Christological exposition (cf. Phil. 2:6–11; Col. 1:15–20), an explanation of Paul’s eschatology (cf. 1–2 Thessalonians), or an unfolding of a Pauline doctrine of the church (see Ephesians; 1 Timothy; Titus). Ephesians may be a circular letter sent to a number of churches, in which Paul sets forth a more comprehensive understanding of the church, but even Ephesians lacks a complete exposition of all of Paul’s theology. We must mine all of Paul’s letters to determine his theology—and God, in his providence, has given us all the letters (and, of course, the whole of Scripture) so that we can understand the “whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:27).

In interpreting the Epistles, then, we should try to understand the specific circumstances that the original readers were facing. Upon reading Galatians, for instance, we see readily enough that Paul is responding to opponents who are subverting the gospel. Our understanding of Paul’s purpose in writing Galatians is sharpened if we piece together the clues in the letter to reconstruct the views of Paul’s opponents. We see that certain outsiders had infiltrated the church and were arguing that the Galatians must submit to circumcision and keep the OT law in order to be saved (cf. Gal. 1:7; 2:3–5; 3:1–14; 5:2–6, 12; 6:12–13). Paul contends vigorously that no one is saved by works of law but only through faith in Jesus Christ.

As readers of the Epistles today, we face a disadvantage that the first readers did not have, for they knew firsthand the situation that the letter writer addressed. Our knowledge of the circumstances is partial and incomplete. Reading the letters can be like listening to half of a telephone conversation: we hear only the writer’s response to the situation in a particular church. Still, we trust that God in his goodness has given us all we need to know in order to interpret the Epistles adequately and to apply them faithfully.

Pseudonymity

Some scholars have argued that the practice of writing a letter in someone else’s name (“pseudonymity”) was culturally accepted in NT times, and hence they claim that some of the NT letters were not written by the purported authors. For example, it is often claimed that Paul did not write 1–2 Timothy and Titus, or that Peter did not write 2 Peter. But the evidence is lacking that pseudonymity was accepted in letters that were considered to be authoritative and inspired. For instance, in 2 Thessalonians 2:2 Paul specifically criticizes those who claim to write in his name, and he concludes the letter with assurance that the writing is authentically his (3:17). The author of the NT apocryphal book Acts of Paul and Thecla was removed from his post as bishop for writing the book as if it were by Paul, even though he claimed that he had written out of love for Paul (Tertullian, On Baptism 17). In the same way, the Gospel of Peter was rejected as an authoritative book in a.d. 180 by Serapion, the bishop of Antioch, because it was not authentic, even though the author claimed that it had been written by Peter. Serapion said, “For our part, brethren, we both receive Peter and the other apostles as Christ, but the writings which falsely bear their names we reject, as men of experience, knowing that such were not handed down to us” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 6.12.1–6).

There is no convincing evidence, then, that pseudonymous writings were accepted as authoritative. Indeed, if Peter did not write 2 Peter, then the author is guilty of deceit and dishonesty because he claims to have been an eyewitness of the transfiguration (2 Pet. 1:16–18) and identifies himself as Peter at the beginning of the letter (2 Pet. 1:1). In the same way, the Pastoral Epistles (1–2 Timothy and Titus) all claim to be by Paul and communicate many details from his life, which would be quite deceptive if Paul did not, in fact, write the letters. Some of the authors may have employed a secretary (amanuensis) to assist them in writing, which might account for some of the stylistic differences in the letters. Still, each letter would have been carefully dictated and reviewed by the apostolic author.