Introduction to Lamentations

Share

INTRODUCTION TO

LAMENTATIONS

This is a book about pain but with hope in God. The author vividly addresses the extremes of human pain and suffering as few other authors have done in history. For this reason, Lamentations is an important biblical source expressing the hard questions that arise during our times of pain. The suffering the author discusses was brought on by the brutal overthrow of Jerusalem in 586 BC, one of the darkest times in Jewish history. When naming a book of the Hebrew Bible, the first word was often adopted as the name of the whole book. In this case, 1:1; 2:1; and 4:1 begin the typical Hebrew cry of woe (Hb ‘ekah, “Ah,” “Alas,” “How”), an exclamatory rather than interrogative Hebrew particle. Thus, the book would have been known as Alas! Later rabbis referred to the book more by its contents—qinot, i.e., “lamentations”—so this title came to be passed down in the Talmud and in the Greek translation (the Septuagint).

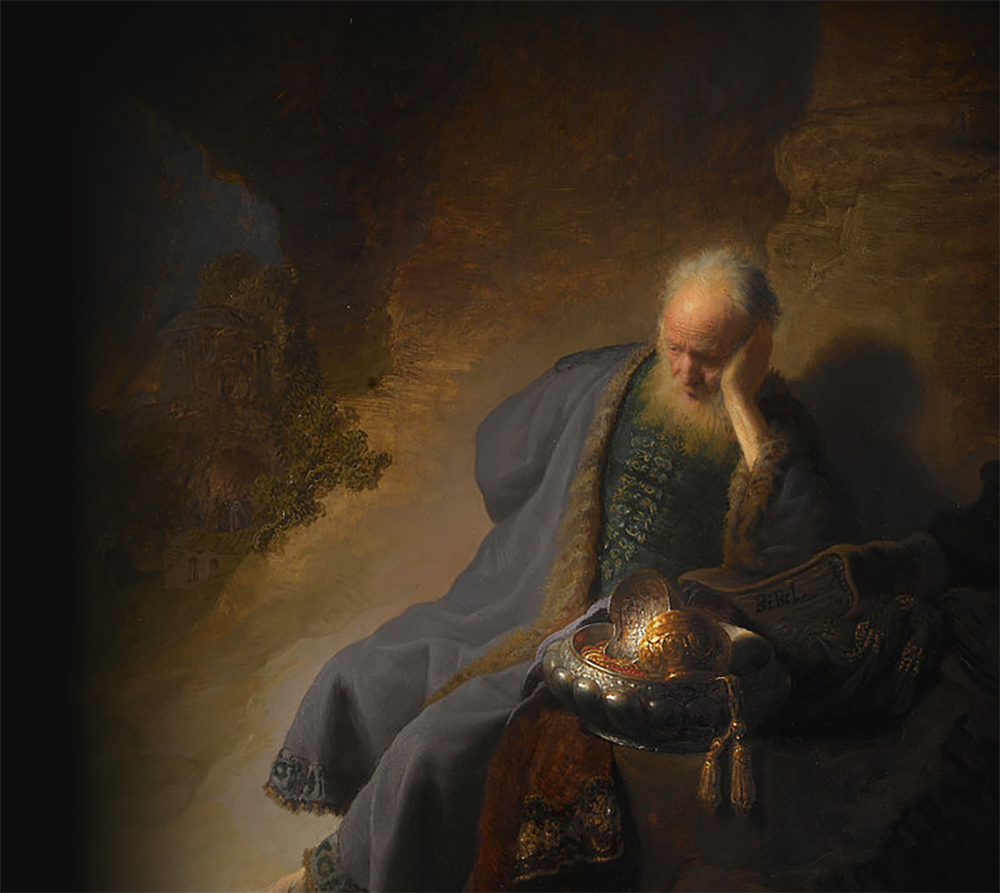

Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem by Rembrandt (1606-1669)

CIRCUMSTANCES OF WRITING

AUTHOR: Jeremiah’s name has long been associated with this book. The Alexandrian form of the Greek Septuagint has these words preceding 1:1: “And it came to pass, after Israel had been carried away captive, and Jerusalem became desolate, that Jeremiah sat weeping, and lamented with this lamentation over Jerusalem.” The Latin Vulgate adds this phrase: “and with a sorrowful mind, sighing and moaning, he said.” The Talmud observes that “Jeremiah wrote his own book and the book of Kings and Lamentations.” Given this rich tradition linking Jeremiah to Lamentations, it seems safe to conclude he did indeed write this book.

BACKGROUND: The sad background for these five poems of lament was the sacking of Jerusalem and the burning of the temple in 586 BC by the Babylonian army. Even though the book lists only one proper name (“Edom,” 4:21-22), the allusions and the historical connections to the events listed so dramatically in 2 Kings 25; 2 Chronicles 36:11-21; and the book of Jeremiah are unmistakable. Perhaps a short list of the key events and some of their allusions in the book of Lamentations will help make this point:

| EVENTS | LAMENTATIONS |

|---|---|

| 1. Siege of Jerusalem | 2:20-22; 3:5,7 |

| 2. Famine in the city | 1:11,19; 2:11-12,19-20; 4:4-5,9-10; 5:9-10 |

| 3. Flight of the Judean army | 1:3,6; 2:2; 4:19-20 |

| 4. Burning of the temple, etc. | 2:3-5; 4:11; 5:18 |

| 5. Breaching of the city walls | 2:7-9 |

| 6. Exile of the people | 1:1,4-5,18; 2:9,14; 3:2,19; 4:22; 5:2 |

| 7. Looting of the temple | 1:10; 2:6-7 |

| 8. Execution of the leaders | 1:15; 2:2,20 |

| 9. Vassal status of Judah | 1:1; 5:8-9 |

| 10. Collapse of foreign help | 4:17; 5:6 |

MESSAGE AND PURPOSE

Lamentations does not offer a complete or understandable explanation for the suffering and pain found here, but it was important that the pain and suffering be connected to the actual events of 586 BC. If these pent-up feelings of agony could not be attached to some datable event, the pain could threaten to take on cosmic proportions. This is why history is necessary. When sorrow becomes detached from history, suffering gets out of hand because perspective is lost, tempting a suffering person to lose touch with reality.

There was more than enough to weep over. The united lament of the people related to their covenant history with God. This anchored their sorrow but also gave their grief specific barriers, lest they should be overwhelmed and lose all hope.

CONTRIBUTION TO THE BIBLE

Few things contrast religious and humanistic traditions more than their respective responses to suffering. The humanist sees suffering as a bare, impersonal event without ultimate meaning or purpose. For believers, suffering is a personal problem because they believe that all events of history are under the hand of a personal God. And if that is true, then how can God’s love and justice be reconciled with our pain?

Lamentations gives no easy answers to this question, but it helps us meet God in the midst of our suffering and teaches us the language of prayer. Instead of offering a set of techniques, easy answers, or inspiring slogans for facing pain and grief, Lamentations supplies: (1) an orientation, (2) a voice for working through grief from “A” to “Z,” (3) instruction on how and what to pray, and (4) a focal point on the faithfulness of God and the affirmation that he alone is our portion.

STRUCTURE

The book of Lamentations exhibits a remarkably fine artistic structure. Each of its five chapters (five poems) is a structurally unified text. The fact that there is an uneven number of poems allows the middle poem (chap. 3) to be the midpoint of the book. Thus, there is an ascent (or crescendo) up to a fixed climax for the entire book, thereby making chap. 3 central in its form and the message it imparts. Accordingly, the first two chapters form the steps leading up to the climax of 3:22-24, and from here there is a descent in chaps. 4 and 5.

The poems or songs of this book also exhibit the so-called chiastic form (a crisscross inversion such as a-b, b-a). As such, chaps. 1 and 5 are overall summaries of the disaster, 2 and 4 are more detailed descriptions of what took place, and chap. 3 occupies the central position.

Lamentations also uses the form of the alphabetic acrostic with the twenty-two-letter Hebrew alphabet. In chap. 5, each of its twenty-two stanzas consists of a single line, but this is the only chapter that is not structured as an alphabetic acrostic.

OUTLINE

I.The City (an Outside View; 1:1-22)

A.Description of Jerusalem’s afflictions (1:1-7)

B.Explanation of Jerusalem’s afflictions (1:8-18)

C.Effect of Jerusalem’s afflictions (1:19-22)

II.The Wrath of God (an Inside View; 2:1-22)

A.Jerusalem’s adversary (2:1-8)

B.Jerusalem’s agony (2:9-16)

C.Jerusalem’s entreaty (2:17-22)

III.The Compassions of God (an Upward View; 3:1-66)

A.The rod of God’s wrath (3:1-20)

B.The multitude of God’s mercies (3:21-39)

C.The justice of God’s judgments (3:40-54)

D.The prayer of God’s people (3:55-66)

IV.The Sins of All Classes (an Overall View; 4:1-22)

A.The vanity of human glory (4:1-12)

B.The vanity of human leadership (4:13-16)

C.The vanity of human resources (4:17-20)

D.The vanity of human pride (4:21-22)

V.The Prayer (a Future View; (5:1-22)

A.Jerusalem invokes God’s grace (5:1-18)

B.Jerusalem invokes God’s glory (5:19-22)

2000-700 BC

Lament for Ur, a Sumerian lament composed after the fall of Ur to the Elamites from the east and the Amorites from the west 2000

The Assyrians sack Babylon. 1240

Samaria, the capital of Israel, captured by the Assyrians 722

Sargon II of Assyria deports 28,000 Israelites and settles them throughout the Assyrian Empire. 722

The Assyrians capture numerous Judean cities—Jerusalem is spared. 701

700-605 BC

Ashurbanipal leads the Assyrians to capture and destroy Babylon. 649

Birth of Jeremiah 640?

Jeremiah is called to be a prophet; he warns of an invasion from the north. 626

The Medes destroy Assyrian capital of Asshur. 614

The Babylonians and Medes destroy the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. Babylon has become the largest city in the world with a population of 200,000. 612

Jeremiah’s temple sermon 609

605-600 BC

Babylonians defeat Pharaoh Neco of Egypt at Carchemish. The Babylonians hold the balance of power in the region. 605

Babylonian force is exercised in the destruction of the Philistine cities of Ashkelon, Ashdod, and Ekron. 604

Jehoiakim makes a decision to turn from his alliance with Egypt and submit to Nebuchadnezzar. 604

Jehoiakim ignores Jeremiah’s warning and turns back to Egypt for support after Egypt defeats Babylon at Migdol. 601

A reinforced Babylonian army approaches Judah; Jehoiakim dies. 598

600-585 BC

Nebuchadnezzar plunders the temple, takes Jehoiachin and the royal family into exile, and Zedekiah becomes king. 597

Nebuchadnezzar destroys Jerusalem and the temple. 586

Nebuchadnezzar appoints Gedaliah as governor of Judah. 585

Judah’s provincial capital is moved from Jerusalem to Mizpah. 585

Gedaliah is assassinated after only two months by a group of fanatically zealous nationalists under the leadership of Ishmael. 585

Lamentations 585