Intertestamental History

Share

INTERTESTAMENTAL HISTORY

R eading the Bible from cover to cover is a rewarding experience. But moving from the last book in the Old Testament (Malachi) to the first book in the New Testament (Matthew) can be puzzling. The experience can be like falling asleep during a movie. You wake up and wonder what happened to the characters you knew. And who are these new characters?

The Gamla Synagogue in the Golan Heights is one of the earliest synagogues in Israel, dating to the first century AD. This was the sight of intense conflict between the Jews and the Romans during the Jewish revolt.

The events recounted in the Old Testament end in the fifth century BC God has scattered the people of Israel because of their disloyalty to him and then brought many of them back to their land. Now called “Jews,” a term hardly used outside Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther, they have been severely oppressed by the Assyrians and Babylonians and are now subjects of the Persian Empire. Their territory has been diminished to Jerusalem and the surrounding areas. They have a new temple, but it pales in comparison to the temple Solomon built. Their local officials are the Jewish governor and high priests aided by other priests and Levites, and they must answer to an occasional prophet (Ezr 3:8-9; Hg 1:1).

When Bible readers come to the New Testament, they find themselves transported into the future four hundred years. Jerusalem has expanded and is now part of the Roman province of Judea (Mt 2:1). Gone are the Persian overlords. In their places are a people from the western Mediterranean—the Romans. Latin and Greek are the languages of the Roman Empire and exist alongside the primary languages of subject peoples—Syriac, Coptic, Hebrew, and Aramaic. The Roman Senate has appointed Herod the Great as “King of the Jews,” and he is in the process of transforming the Jewish temple into one of the architectural wonders of the world. A high priest is still chief of all the priests officiating at the Jerusalem temple. The high priest presides over a seventy-one-member council, the Sanhedrin, composed of both parties of the Jews—predominantly Sadducees but also leading Pharisees. The voice of prophecy hasn’t been heard since Malachi, but an important new institution is present in Jewish society—the synagogue.

All these changes took place in the four hundred-year period between Malachi and Matthew, a time span sometimes called the inter-biblical or intertestamental period. This period fits within the Second Temple Period—the late sixth century BC to the late first century AD Having an overview of the key events, persons, and issues of this period will enhance one’s grasp of the continuity between the Old Testament and the New Testament, and will help avoid one of the first heresies of the Christian church, promoted by Marcion of Sinope, who denied that there is continuity between the Hebrew Scriptures and the gospel.

The history of the intertestamental period can be divided into four sections: the Persian period, 539-323 BC; the Greek period, 323-167 BC; the Period of independence, 167-63 BC; and the Roman period, 63 BC through the time of the New Testament.

THE PERSIAN PERIOD, 539-323 BC

Shortly after 600 BC the Babylonians captured Jerusalem, destroyed the temple, and took away many of the people as captives. Almost immediately after Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylonia in 538 BC, he allowed the Jews who so desired to return to their homeland. Cyrus issued a decree authorizing the Jerusalem temple to be rebuilt. He returned to the Jerusalem temple the gold and silver vessels that Nebuchadnezzar had taken to the house of his god in Babylon around 605 BC. Cyrus died in 530 BC; however, the Persian Empire continued to grow. Cambyses II (530-522 BC), Cyrus’s son, conquered Egypt in 525 BC but found it difficult to administer. When Cambyses died, Darius I made a strong case for being his legitimate successor. At the time Darius assumed power, the Persian Empire was showing signs of disintegration. Darius rose to the challenge and firmly establish himself as ruler of the empire. He extended his empire from northern India in the east to the Black Sea, parts of Greece, Cyprus, and Libya in the west. Darius attempted to invade Greece on two occasions. His first attempt was thwarted by a storm at sea. In the second, he lost to the Greeks at Marathon in 490 BC. Later emperors did little to expand Persian territory.

By the time of Darius I (522-486 BC), the empire was highly organized, divided into twenty satrapies (political units of varying size and population). Satrapies were subdivided into provinces. Initially Judah was a province in the satrapy of Babylon. Later Judah was in the province called Trans-Euphrates (“Beyond the River”). The satrapies were governed by Persians directly responsible to the emperor. The Persian imperial postal system, built on a network of quality roads, was the first of its kind and facilitated the effective administration of this vast empire.

Darius continued Cyrus’s policy of restoring to their native lands peoples who had been displaced by Assyrian and Babylonian conquests. He reaffirmed Cyrus’s authorization to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem and provided imperial funds for the project. The temple was completed in the sixth year of his reign.

Darius was succeeded by his son Xerxes who reigned 486-464 BC. Xerxes is known in the book of Esther as Ahasuerus. He sought and ultimately failed to avenge his father’s defeat at the hands of the Greeks. Later the focus of his reign was maintaining the empire’s roads, especially the 1775-mile Royal Road that ran from Susa on the lower Tigris River to Smyrna on the Aegean Sea. An inordinate share of the empire’s resources was spent on building projects in Susa and Persepolis. The grandeur of these projects was designed to secure Xerxes’s place in history. Ironically, the costs of these enterprises coupled with his military campaigns against the Greeks only hastened the decline of the empire.

The leadership of Ezra and Nehemiah in Jerusalem took place during the long reign of Xerxes’s son, Artaxerxes I (464-424 BC). Early in his reign, Artaxerxes received a letter from Rehum, a Persian official in Judah, asking him to stop the rebuilding of the city. The letter urged him to do some research on the history of Jerusalem contained in his father’s archives. This research would show the people of Jerusalem have a pattern of rebelling against kings. To allow them to build a strong city would run the risk of Persia losing not only Jerusalem but everything west of the Euphrates.

Artaxerxes’s initial response to the letter was to order reconstruction of Jerusalem halted. However, six years into his reign (458 BC) he dispatched Ezra and a large company of Israelites to Jerusalem (Ezr 7:7). Ezra’s passion was to study the law of the Lord, practice it, and teach his fellow Israelites to understand the law and its implications for their lives (Ezr 7:10). Some scholars have speculated that Artaxerxes’s motivation may have been to create a strong satrap centered in Jerusalem that would further Persian interests by controlling Egypt and serving as a regional buffer against armies to the west of Judah. Thirteen years later, Artaxerxes granted his trusted cupbearer Nehemiah’s request to return to Jerusalem to participate in and lead the continued reconstruction of the city. Artaxerxes made Nehemiah governor of Judah (Neh 5:15).

THE GREEK PERIOD, 323-167 BC

The Persian Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great in 538 BC, lasted two centuries. About 350 BC Philip II came to the throne of Macedonia, a territory in what is now largely northern Greece. Philip brought the entire Greek peninsula under his control, only to be assassinated in 336 BC. He was succeeded by his nineteen-year-old son, Alexander III (the Great), whose schoolmaster had been the great philosopher, Aristotle. Within two years Alexander set out to conquer the far-reaching Persian Empire. In a series of battles over the next two years, he gained control of the territory from Asia Minor to Egypt. This included Palestine and the Jews. Alexander’s conquest had three major results.

First, he introduced Greek ideas and culture into the conquered territories. This is called hellenization. He believed that the way to consolidate his empire was for the people to have a common way of life. However, he did not seek to change the religious practices of the Jews. This toleration applied to Jews who served in his army. When Alexander came to Babylon and saw the declining state of the temple of Marduk, he pressed his soldiers into rebuilding this temple. The Jews among his troops objected to participation in the project. Alexander honored their religious sensibilities and did not force them to work on the pagan temple.

Second, he founded Greek cities and colonies throughout the conquered territory. When he established the new city of Alexandria in Egypt, he moved many Jews from Palestine to populate one part of that city. Third, he spread the Greek language into that entire region so that it became a universal language during centuries that followed. By 331 BC Alexander had gained full control over the Persian Empire.

When Alexander died in 323 BC, power struggles among his generals ensued. Each general took a portion of the vast empire. Over nearly half a century (322-275 BC) numerous battles were fought between Alexander’s successors, each seeking to gain a larger share of the empire. Ptolemy, a Macedonian companion of Alexander, ruled Egypt initially in place of Alexander’s half-brother and his son, Alexander IV. With the passing of time, he designated himself pharaoh of Egypt—Ptolemy I Soter.

Another of Alexander’s generals, Seleucus claimed parts of Asia Minor, Syria, and the territories as far east as the Indus River. Both Ptolemy and Seleucus and their heirs had designs on Palestine, which each saw as rightfully theirs. For all practical purposes, Ptolemy I Soter of Egypt and his successors ruled Palestine until around 200 BC. The Judeans fared well under the Ptolemies. They had a high degree of self-rule in which the high priest and a council of elders governed the province according to the law of Moses. Ptolemy granted considerable latitude to the Judeans for the practice of their religion. During this time Jewish men in the vicinity of Jerusalem made three visits to the temple annually. Those of the Diaspora sent an annual temple tax of half a shekel for the maintenance of the temple.

Ptolemy I Soter, Alexander the Great’s general, king of Egypt (305-282 BC) and founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty

Ptolemy brought a large number of Judeans to Egypt, some thirty thousand of whom he enlisted as soldiers. He had a higher level of trust with the Judeans than he did with soldiers native to Egypt. He annexed Cyrenaica, a territory that included the city of Cyrene, five hundred miles west of Egypt. Here he posted Judean soldiers to ensure loyalty of the local population and serve as a buffer against rival rulers. This colony of Judean soldiers was the beginning of a significant Jewish Diaspora in North Africa.

As Macedonians, the Ptolemies spoke Greek and made it the official language of the territories they governed. Judeans who emigrated to Egypt, Cyrene, and Cyprus may have continued to converse among themselves in Aramaic, but they likely learned Greek in order to participate in regional and international commerce. Greek then became the primary language of their descendants. Growing Jewish presence in places where Greek was the primary language created the need for the Hebrew Scriptures to be translated into Greek. This translation was called the Septuagint.

Septuagint is derived from the Greek word for “seventy.” According to the legendary account set forth in the Letter of Aristeas, around 270 BC Ptolemy II Philadelphus, a patron of the arts, letters, and scientific inquiry, brought seventy-two Jewish translators from Jerusalem to Egypt to translate the Pentateuch into Greek. Other books of the Hebrew Bible were translated into Greek over the next two centuries. These translations varied in accuracy and style—some highly literal; others free, interpretive, and some books closer to paraphrases. In Invitation to the Septuagint, Karen Jobes and Moisés Silva point out that the term Septuagint functions as a generic expression—more like “the English Bible” rather than referring to a single work like the King James Version—despite the fact that the popular use of the term gives the impression of referring to one specific work.

Ptolemy II Philadelphus ruled Egypt 285-246 BC. He was a patron of the arts and sciences, expanded the Library at Alexandria, and sponsored the translation of the Torah into Greek.

Palestine continued as part of the Ptolemaic kingdom through the third century BC. From the time of Alexander’s death, the Seleucids, who originally made Babylon the foundation of their empire, coveted Palestine, the land bridge connecting Asia, Africa, and Europe. Antiochus III (the Great) moved toward that goal during the Fourth Syrian War (219-217 BC) but suffered defeat at Raphia in 217. However, at the battle of Panion (200 BC), Antiochus defeated Ptolemy IV. Antiochus’s borders now extended through Palestine to Egypt. Like the Ptolemies, Antiochus allowed the Jews to practice their religion freely. For a time, he eliminated their taxes that had become excessive under the Ptolemies’ rule.

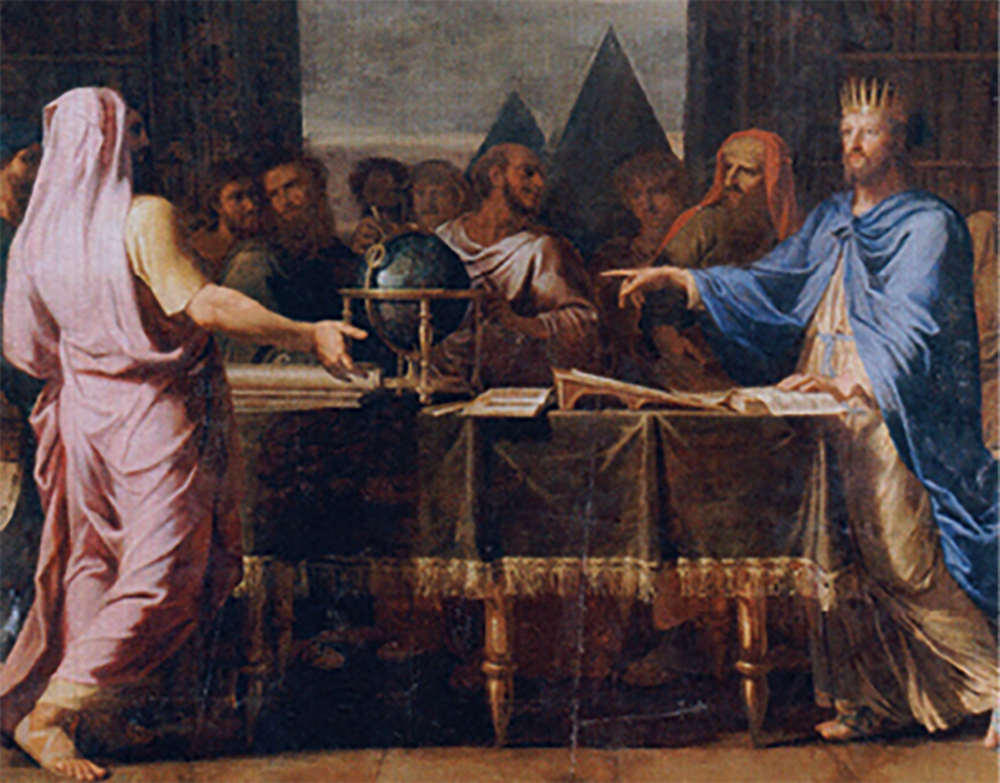

Ptolemy II Philadelphus conversing with some of the 72 Jewish scholars who translated the Hebrew Bible into Greek. Artist: Jean Baptiste de Champaigne (1631-1681). This was the Bible of many of the early Christians and is quoted heavily in the New Testament.

Just as the Ptolemies created a large Jewish Diaspora in Egypt and across North Africa, Antiochus III initiated a pattern of Jewish emigration to and settlement in Asia Minor. According to Lawrence Shiffman, Antiochus took two thousand Jewish families who were living in Babylonia and settled them in Lydia and Phrygia as military colonists around 210-205 BC. The exact location of and number of persons in each settlement is unknown. Creating these kinds of colonies was designed to pacify the region, defend frontiers, and protect trade routes and lines of communication. Antiochus had a high level of confidence that these families would be loyal to his interests in Asia Minor. These families—descendants of those who had been taken to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar—had grown up outside Palestine. Their forbearers had assimilated with Gentile cultures, while maintaining some of the essentials of their faith.

Greek coin weighing eight drachmas and bearing the likeness of Antiochus III, king of the Seleucid Empire

Jews from these and other provinces in the northern tier of the Mediterranean Basin were at the Feast of Pentecost in AD 33 and heard Peter’s witness to the death and resurrection of Jesus and the invitation to repent, be baptized, receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. From a Jewish community in the Roman province of Cilicia came one of Christianity’s most important interpreters, Saul of Tarsus.

While many Judeans welcomed Seleucid rule, the situation changed after Antiochus was defeated by the Romans in the battle of Magnesia, 190 BC. Antiochus had supported Hannibal of North Africa, Rome’s arch enemy. As a result, Antiochus had to give up all of his territory except the province of Cilicia. He had to pay a large sum of money to the Romans for a period of years and surrender his navy and elephants. To guarantee his compliance, one of his sons was kept in Rome as a hostage. So the tax burden of the Jews increased, as did pressure to hellenize, that is, to adopt Greek language and culture.

Antiochus was succeeded by his son Seleucus IV, 187-175 BC. When he was murdered, his younger brother became ruler. Antiochus IV, 175-163 BC, was called Epiphanes (“manifest” or “splendid”), though some called him Epimanes (“mad”). He was the son who had been a hostage in Rome. During the early years of his reign, the situation of the Jews became worse. They were divided over the issue of hellenization. Some Jewish leaders, especially the priests, encouraged hellenization, while others strongly opposed it.

Up to the time of Antiochus IV, the office of high priest had been hereditary and held for life. However, Jason, the brother of the high priest, offered Antiochus a large sum of money to be appointed high priest. Antiochus needed the money and made the appointment. Jason offered an additional sum to receive permission to build a gymnasium near the temple. Within a few years, Menelaus, a priest but not of the high priestly line, offered the king more money to be named high priest in place of Jason. He stole vessels from the temple to pay what he had promised.

To keep the Ptolemies in check, Antiochus invaded Egypt and took control of most of the country with the exception of Alexandria, the capital. This action displeased the Roman Senate that dispatched an ambassador, Gaius Popillius Laenas, to confront Antiochus and force him to decide whether he would advance on Alexandria or withdraw from Egypt. Not wanting a direct conflict with Rome, he withdrew.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes of Syria

When Antiochus reached Jerusalem, he found that Jason had driven Menelaus out of the city. Antiochus viewed this as full revolt. He invaded the city and allowed his troops to kill many of its residents. Determined to put an end to the Jewish religion, he sacrificed a pig on the altar of the temple. Parents were forbidden to circumcise their sons, the Sabbath observance was prohibited, and all copies of the law were to be burned. It was a capital offense to be found with a copy of the law. The zeal of Antiochus to destroy Judaism was a major catalyst in the Maccabean revolt.

Part of a Hasmonean era coffin uncovered during archaeological excavations outside the city of Modein

JEWISH INDEPENDENCE, 167-63 BC

Resistance was passive at first, but when the Seleucids sent officers throughout the land to compel leading citizens to offer sacrifices to Zeus, open conflict flared. It broke out first at the village of Modein, about halfway between Jerusalem and Joppa. An aged priest named Mattathias was chosen to offer the sacrifice. He refused, but a young Jew volunteered to do it. This angered Mattathias, and he killed both the young Jew and the officer who ordered the sacrifice. Mattathias then fled to the hills with his five sons and others who supported his action. The revolt had begun.

Leadership fell to Judas, the third son of Mattathias. He was nicknamed Maccabeus, the hammerer. He probably received this title because of his skill as a warrior. He was the ideal guerrilla leader, fighting successful battles against much larger forces. A group called the Hasidim made up the major part of his army. These men were devoutly committed to the worship of God, the law of God, and to religious freedom.

Shortly before the revolt of Judas Maccabeus (2Macc 8), Antiochus IV Epiphanes arrested a mother and her seven sons, and tried to force them to eat pork. When they refused, he tortured and killed the sons one by one. The narrator mentions that the mother “was the most remarkable of all, and deserves to be remembered with special honour. She watched her seven sons die in the space of a single day, yet she bore it bravely because she put her trust in the Lord” (2Macc 7:20, NEB). The narrator ends by saying that the mother died. He did not say whether she was executed or died in some other way.

Antiochus IV was more concerned with affairs in the eastern part of his empire than with what was taking place in Palestine. Therefore, he did not commit many troops to the revolt at first. Judas was able to gain control of Jerusalem within three years. The temple was cleansed and rededicated exactly three years after it had been polluted by Antiochus (ca 164 BC). This event is still commemorated by the Jewish feast of Hanukkah or the feast of Dedication (Jn 10:22-23). The Hasidim had gained what they were seeking—religious freedom—and so they put down their arms, but Judas had a larger goal in mind—an independent Jewish state. He rescued mistreated Jews from Galilee and Gilead and made a treaty of friendship and mutual support with Rome. In 160 BC at Elasa near modern day Ramallah, with a force of eight hundred men, he fought a vastly superior Seleucid army and was killed.

Judas Maccabeus before the army of the Syrian general, Nicanor

Jonathan, another son of Mattathias, took the lead in the quest for independence. He did not have the military skills of Judas, but he excelled at diplomacy. Jonathan was appointed high priest and so Jewish religious and civil rule were centered in one person. Jonathan was taken prisoner and killed in 143 BC.

Simon, the last surviving son of Mattathias, conquered strategic military strongholds, secured freedom from taxation for the Jews, and won other concessions from Seleucid rulers that led to an independent Jewish state in 142 BC. Simon was acclaimed by the people as their leader and high priest. The high priesthood was made hereditary with him and his descendants. He ruled until 134 BC when he was murdered by his son-in-law in a coup.

This independent Jewish state lasted until 63 BC, governed by Simon and his descendants. This period is called the Hasmonean Dynasty, named after Mattathias’s great-grandfather Asamoneus. When Simon was assassinated, his son John Hyrcanus became the high priest and civil ruler from 134-104 BC. The oldest son of Hyrcanus, Aristobulus I (104-103 BC), succeeded him and imprisoned all of his brothers and his mother, who later starved to death. When Aristobulus died, the eldest of his imprisoned brothers, Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC), succeeded him. Jannaeus took his brother’s widow, Salome Alexandra, in marriage. He was an ambitious warrior and conducted campaigns by which he enlarged his kingdom to about the size of King David’s, including territory in Cisjordan and Transjordan from Upper Galilee to the Dead Sea. However, his rule was characterized by internal strife to the point of civil war. According to Josephus (J.W. 1.97; Ant. 13.380), Jannaeus crucified eight hundred of his Pharisee antagonists and had their families executed before their eyes.

Alexandra succeeded Jannaeus as ruler (76-67 BC). Since she could not serve as high priest, the two functions were separated. Her oldest son, Hyrcanus II, became high priest. When Alexandra died, civil war broke out and lasted until 63 BC. Her younger son, Aristobulus II, easily defeated Hyrcanus, who was content to retire. This might have been the end of the story were it not for Antipater, an Idumean and father of Herod the Great. He persuaded Hyrcanus to seek the help of Aretas III of Nabatea to regain his position. Aretas and his Nabatean Arabs invaded Palestine and besieged Jerusalem with Aristobulus inside. This conflict between Alexandra’s sons provoked Rome’s intervention. Both Aristobulus and Hyrcanus appealed to Scaurus, Pompey’s military tribune charged with the administration of Palestine. When the Roman general Pompey arrived later, both Aristobulus and Hyrcanus made their cases to him.

THE ROMAN PERIOD, 63 BC-THE NEW TESTAMENT ERA

In 63 BC, Pompey seized control of Jerusalem, reinstated Hyrcanus as high priest, and sent Aristobulus to Rome as a prisoner. Hyrcanus (67-66; 63-40 BC) was permitted to remain as ethnarch, but under Roman oversight. This began the Roman occupation and control of Judea and the surrounding territories for the purpose of securing this strategic land bridge that permitted freedom of movement for their armies and protected their commercial interests to the east. Roman power was exercised through Antipater, who was eventually named governor of Judea by Julius Caesar in response to his support of Caesar’s efforts in Egypt. Hyrcanus continued to serve as high priest.

While Palestine was successively under the control of various Roman officials, Antipater was the stabilizing force. To his son, Phasael, he handed over the administration of Jerusalem; to his second son, Herod, he gave authority in Galilee. The latter quickly earned a reputation as a firm, at times brutal, ruler. He was able to bring order to his territory and evade any charges brought against him for his authoritarian ways. Antipater was murdered in 43 BC; shortly thereafter, Herod and Phasael were named tetrarchs over Galilee and Judea respectively by the new commander of the eastern Roman Empire, Mark Antony. In 40 BC, the Parthians invaded Palestine and made the Hasmonean Antigonus, the last surviving son of Aristobulus II, king of Palestine. His uncle, Hyrcanus II, was mutilated on the order of Antigonus so that he could no longer serve as high priest. Phasael was captured and committed suicide in prison. Herod barely escaped with his family whom he left with other loyalists atop the Judean Desert fortress, Masada, while he sailed to Rome to seek assistance. He had intended to seek rule over the region on behalf of his wife’s brother, Aristobulus III, who was of the Hasmonean line. However, the Roman Senate, at the urging of Antony and Octavian (Augustus), made Herod king in 40 BC. Upon his return, Herod secured himself in Galilee and retrieved his family from Masada. However, it took him three years to drive the Parthians out of the country and establish his rule. He was king until his death in 4 BC.

Model of the northern palace of Herod the Great at Masada

The years of Herod’s rule brought turmoil for the Jewish people. He was nobility but of Idumean descent. His ancestors had been forced to convert to Judaism under John Hyrcanus, but the Jewish people never accepted him as their ruler: He was viewed as the representative of a foreign power—Rome. Even his marriage to Mariamne, granddaughter of Aristobulus II, gave no legitimacy to his rule in the sight of the people. Herod had many problems that grew out of his jealousy and paranoia. He had Aristobulus III, his brother-in-law, executed. Later Mariamne, her mother, and his two sons by Mariamne were killed because Herod viewed their Hasmonean lineage as a threat. Furthermore, just days before his own death, Herod had his eldest son Antipater put to death. His relations with Rome were also sometimes troubled due to the unsettled conditions in the empire. Herod was a strong supporter of Antony, even though he could not tolerate Cleopatra, with whom Antony had become enamored. When Antony was defeated by Octavian in 31 BC, Herod went to Octavian and pledged his full support. This support was accepted, and Herod proved himself an efficient administrator on behalf of Rome. He kept the peace among a people who were difficult to govern. He also had an impressive building program, which he used to introduce western architectural elements across his kingdom. Herod constructed fortresses, palaces, aqueducts, stadiums, amphitheaters, and even entire urban areas. Of note are the Antonia Fortress, Masada, Herodium, and Machaerus; his palaces at Masada, Herodium, Jerusalem, and Jericho; and the cities of Sebaste in Samaria and the port city of Caesarea Maritima on the Mediterranean coast, featuring extensive artificial breakwaters built to create the large harbor there. His most impressive construction, however, was the renovation of the temple mount and the Jerusalem temple. Though Herod was a cruel and merciless man, his elaborate building efforts, relatively peaceful rule, and occasional generosity provided stability and benefit to the regions under his rule. By the end of his life his reign extended from Idumea in the south to Iturea in the north and well into Transjordan, rivaling the Hasmonean state in wealth and territory at its largest extent under Alexander Jannaeus.