The Historical Reliability Of The Old Testament

Share

THE HISTORICAL RELIABILITY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT

Kenneth A. Kitchen

“R eliability” is the quality of being dependable and truthful. Is the Old Testament (OT) reliable in what it says about God’s dealings with humanity in the ancient Near East? Discoveries from that early world often illustrate the factual reality of OT history.

PRIMEVAL HISTORY

Shared memories represent one proof of the reliability of the OT. Far antiquity saw the passing of countless human generations, but they kept a living memory of momentous events. For instance, other cultures told stories that are strikingly similar to Noah’s flood. This is indirect proof for the reliability of the OT. The Genesis schema of documenting creation and listing two sets of eight or ten representative generations living before and after the flood also finds commonality in ancient Sumerian and Babylonian literature. This demonstrates that the OT fits the literary forms and practices of the era it documents. Finally, long lives like Methuselah’s 969 years are no bar to personal historicity; ancient Sumerian documents maintain that King (En)-me-bara-gisi reigned for 900 years. The 900-year reign is not credible, but King (En)-me-bara-gisi was not fictional. He is known to be historical because archaeologists have discovered inscriptions bearing his name. It was a widespread ancient convention to “stretch” spans of true events and ages of people that hailed from primeval times.

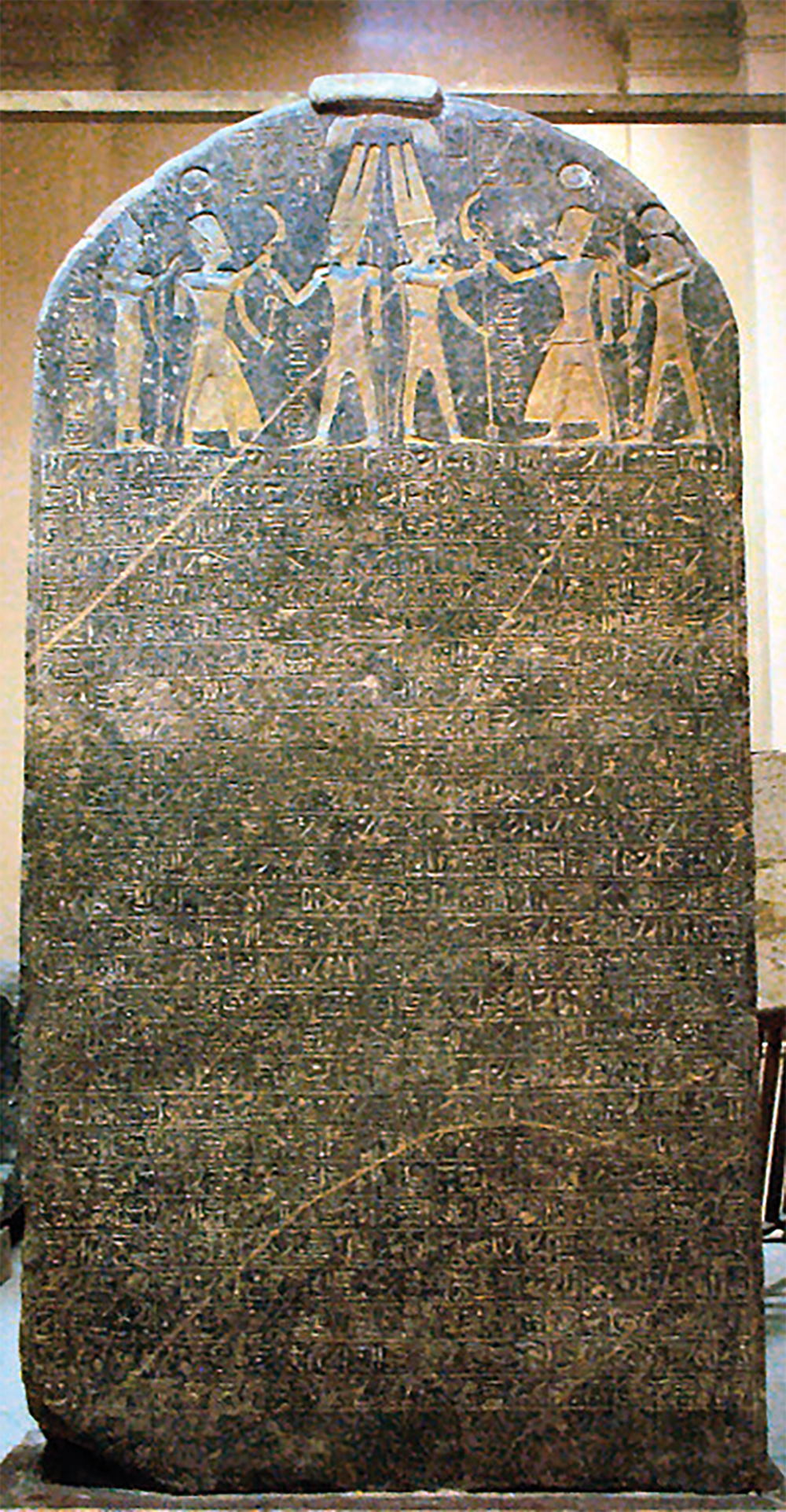

The Merneptah Stele (above) dates to the late thirteenth century BC. Pharaoh Merneptah (1212-1203 BC) memorializes his victories against Libya and in Canaan on this granite stele. Outside the Bible, this is the earliest reference to Israel to date: “Israel is laid waste, its seed is not.” The Merneptah Stele was discovered in 1896 by Flinders Petrie at Thebes and is currently in the Cairo Museum, Egypt.

PATRIARCHAL HISTORY

With Abraham we enter the era of the patriarchs (ca 2000-1600 BC). Historical records are more plentiful from this point on in history. The patriarchs herded sheep and cattle, ranging from Ur (modern Iraq) down to Egypt. Data from Ur during this era record large flocks of sheep, which fits with OT depictions. Archives from Mari mention Haran, where Abraham once lived. From the time of Abraham down to Jacob, Canaan was a land of independent “city-states” like Shechem, (Jeru)salem, and Gerar. These population centers were sustained by pastures, frequented by local herdsmen and visitors like Abraham and his descendants (Gn 37:12-13). Egyptian “execration-texts” provide extrabiblical evidence of this practice. The war between the Canaanite kings and eastern rulers from Babylonia (Shinar, Ellasar—see Gn 14) and Iranian Elam is true to this period. The Mari archives verify that this was the only period in which Elam’s forces reached so far west and when many war alliances flourished. Patriarchal customs involving things like marriage and covenant-formation reflect this period, as does the sum of 20 shekels paid to purchase Joseph (Gn 37:28). Egyptian details mentioned in the OT (personal names, deadly famines, the practice of “reading” dreams, etc.) match what is learned about Egypt from other ancient sources.

In Egypt the enslaved Hebrews labored to build cities such as Rameses and Pithom. One view is that this took place under Ramesses II (1279-1213 BC). Another view is that the exodus took place around 1446 BC. Archaeology reveals that Rameses included chariotry-stables (see Ex 14:25). During the exodus from Egypt, God led the Hebrews not by the nearby northern route to Canaan (cp. Ex 13:17-18), which was infested with Egyptian military stations, but by Mount Sinai, which was safely south of Egyptian control.

The covenant Moses mediated between God and Israel at Mount Sinai includes features (historical introduction, identification of witnesses, the naming of covenant blessings and curses) that reflect known usage in the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BC, and the tabernacle (Ex 25:9; 26:1ff) echoes a long regional tradition (ca 2800-1000 BC) of building sacred tents and sanctuaries. By 1209 BC, tribal Israel was already in Canaan. Extrabiblical proof for this is found on Pharaoh Merneptah’s Victory Stele.

HISTORICAL ISRAEL

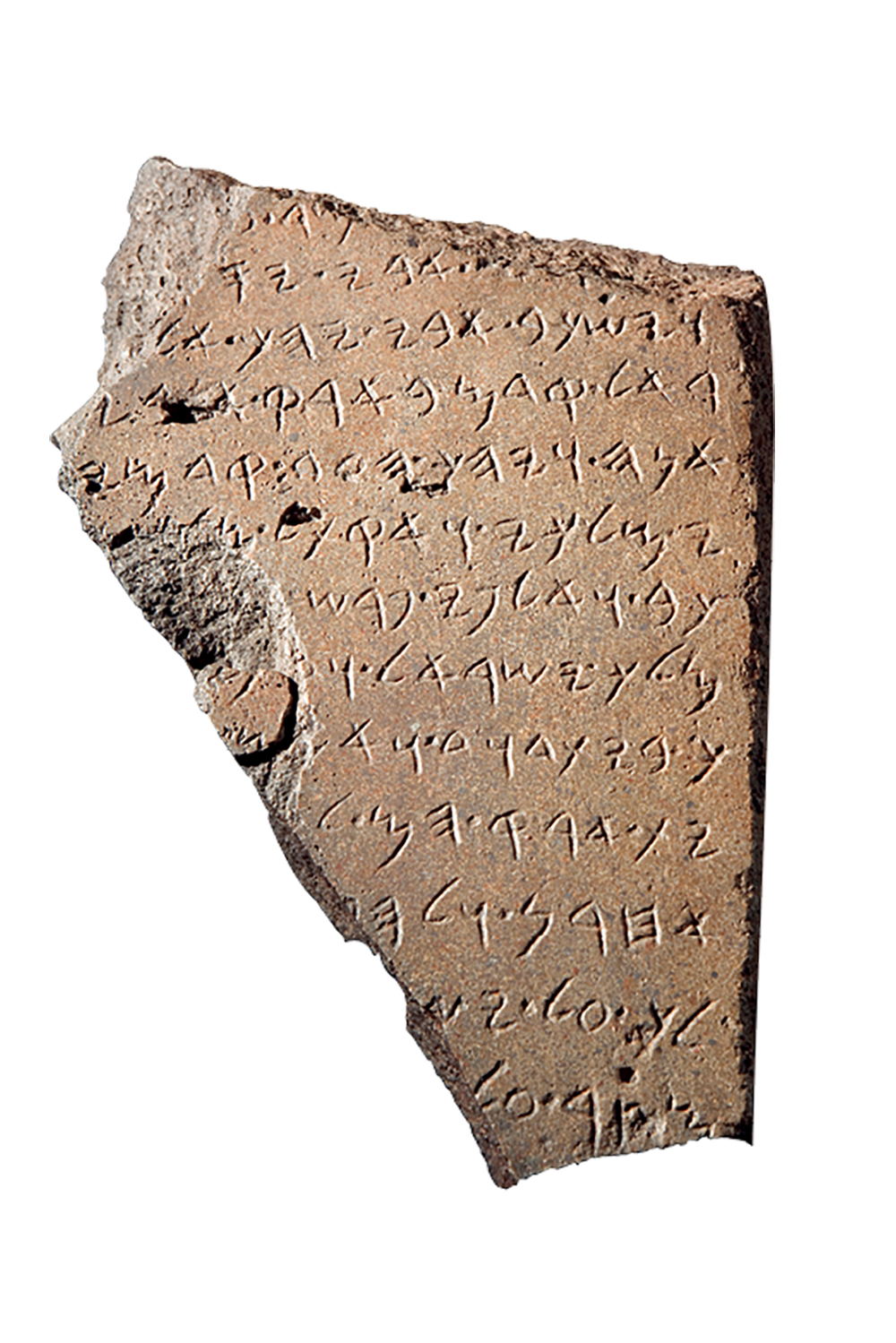

After the troubled times of the judges, Saul, David, and Solomon ruled Israel. “The House of David” is named on an Aramean stele from Dan, and likewise on the stele of Mesha, king of Moab. Less than 50 years after David, the place-name “Heights of Davit” (Egyptians used t for final d) is included in the geographic list of Palestine drawn up for Shoshenq I (“Shishak” ca 924 BC). The design of Solomon’s temple reflected trends that were current in neighboring Syria, though the temple’s décor was modest by comparison. Solomon’s wisdom-writings fit his epoch in format and content.

After Solomon’s death (930 BC), Israel and Judah split into two kingdoms. The Assyrians advanced southward and came into repeated contact with Hebrew rulers. Thus Ahab and Jehu of Israel are mentioned in texts of Shalmaneser III, while his successors mention Jehoash, Menahem, Pekah, and Hoshea. We have Hebrew seals identifying servants of Jeroboam II and Hoshea. From Judah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah are included on official seal-impressions, while Assyrian records name (Jeho)-ahaz, Hezekiah, and Manasseh. All these kings appear in the same sequence and epochs in both biblical and Assyrian records.

Mesha of Moab left a stele mentioning Omri and Ahab of Israel. In turn, the narratives in Kings and Chronicles mention, in correct periods and order, the following kings of Egypt: Shoshenq I [Shishak], Osorkon IV [So], Taharqa [Tirhakah], Neco (II), and Hophra [Apries]. Also mentioned are Assyrian rulers Tiglath-pileser III, Shalmaneser (V), Sargon (II), Sennacherib, and Esar-haddon. Finally, the Babyloni-an rulers Merodach-baladan (II), Nebuchadrezzar (II), and Evil-merodach are named. Various events are documented in both biblical and external sources through 200 years for Israel and 340 years for Judah. The falls of Samaria (722/720 BC) and Judah (605-597 BC) are mentioned in Assyrian and Babylonian chronicles respectively.

The House of David Inscription is the earliest reference to David outside the Bible. This inscription was part of a victory monument erected by an Aramean king in the ninth century bc. He celebrates victories over a “king of Israel” and a king of the “House of David”—a reference to Judah. This artifact was discovered in 1994 at Tell Dan in Northern Israel. It resides currently in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

We have discovered ration-tablets from Babylon for the banished Judean king Jehoiachin and his family for 594-570 BC. The well-documented Persian triumph in 539 BC enabled many exiles to return to Judah and rebuild Jerusalem and its temple, just as the OT says. Other biblical figures now verified through archaeological discoveries include: Sanballat I of Samaria from Aramaic papyri; the later family of Tobiah of Ammon from tombs at Iraq al-Amir; and Gashmu/Geshem as an Arabian king in Qedar, from a bowl belonging to his son Qaynu.

The historicity of the OT should be taken seriously. As for the OT text itself, the Dead Sea Scrolls (ca 150 BC-AD 70) provide good evidence of a carefully transmitted core-text tradition through almost a thousand years down to the Masoretic scribes (ca eighth-tenth centuries AD). Thus, the basic text of OT Scripture can be established as essentially soundly transmitted, and the evidence shows that the form and content of the OT fit with known literary and cultural realities of the ancient Near East. For more, see K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament.